13.3622° N, 103.8597° E

Cambodia Dispatches

Flying out. Flying in.

Seven hours wandering the beige halls of Don Mueang International Airport, inhabiting the same cracked-tile toilets and coffee-stained bench sofas I used to kill time on more than 20 years ago. Down these halls the ghosts of travellers scurry, chasing flights to elsewhere in Asia and beyond. Another era, when travellers wrote postcards and carried their lives on their backs for as long as it took them to run their years of savings dry, or just grow tired and weary of life on the road and return home, financially wiped out but millionaires, spiritually-speaking.

Now, as the saffron disk of dawn climbs above Bangkok, I watch the stampeding hordes of newly-rich Chinese, arms full of DFS stuff, racing and shouting to catch their planes home, and I have flashbacks of first arriving in Asia, hailing a late-night taxi into Bangkok’s dark, steamy maw, passing truck crashes and beggars, durian vendors and clusters of cigarette-puffing tuk-tuk drivers - constellations of pin-pricks of red light in the night.

And so seven hours of memories fade into the hollow PA announcement of the ground staff making the boarding call for the one-hour flight to Siem Reap. The plane goes up, the planes goes down. A pre-lunch beer to ease my nerves, to settle that familiar mix of excitement, cautiousness and calm of landing in unfamiliar territory. The land rises up to meet me: flat, palm studded, with clusters of stilted farm houses clutching dusty roads, and beyond them green paddy lands crisscrossed by rivers and canals, a legacy of the ancient Kingdom of Khmer. Ponds like broken mirror shards cover the farmland, bomb craters made by the Americans during the 70s. Overflow from Vietnam, but which now harbor prawns, ducks and catfish. From death springs life.

Now, as the saffron disk of dawn climbs above Bangkok, I watch the stampeding hordes of newly-rich Chinese, arms full of DFS stuff, racing and shouting to catch their planes home, and I have flashbacks of first arriving in Asia, hailing a late-night taxi into Bangkok’s dark, steamy maw, passing truck crashes and beggars, durian vendors and clusters of cigarette-puffing tuk-tuk drivers - constellations of pin-pricks of red light in the night.

And so seven hours of memories fade into the hollow PA announcement of the ground staff making the boarding call for the one-hour flight to Siem Reap. The plane goes up, the planes goes down. A pre-lunch beer to ease my nerves, to settle that familiar mix of excitement, cautiousness and calm of landing in unfamiliar territory. The land rises up to meet me: flat, palm studded, with clusters of stilted farm houses clutching dusty roads, and beyond them green paddy lands crisscrossed by rivers and canals, a legacy of the ancient Kingdom of Khmer. Ponds like broken mirror shards cover the farmland, bomb craters made by the Americans during the 70s. Overflow from Vietnam, but which now harbor prawns, ducks and catfish. From death springs life.

Good as gold, Mister Saat

Weddings, parties, anything. The amiable Mister Saat

Weddings, parties, anything. The amiable Mister Saat

Siem Reap International Airport. Across the blistering tarmac and into the sweat-smelling bunker of bureaucratic formality to have my visa issued and my passport fingered by an Orwellian line of rubber stampers, sticker-putters and red pen wielders who might, with practice, make an entertaining rhythm section in another world.

Mister Saat is waiting for me among a knot of tuk-tuk drivers, hotel chauffeurs and other hopefuls. He holds a placard with my name. Above it his golden tooth gleams in the midday sun. His skin is the colour of kangaroo jerky - nut-brown with a matt finish. This is a man who spends his working days under the big Cambodian sun. This is a man who at 16 marched off to fight the Khmer Rouge in the northern jungles, leaving behind school and family for a soldier’s life. In that time he mastered the weapons of war: the AK47, M16, M60 and the 37mm anti-aircraft gun (a one-year training course), before spending his final years clearing Russian and Chinese-made mines in rural lands. Never shot anyone, he says. Only a python or two. His golden tooth gleams.

Mister Saat is waiting for me among a knot of tuk-tuk drivers, hotel chauffeurs and other hopefuls. He holds a placard with my name. Above it his golden tooth gleams in the midday sun. His skin is the colour of kangaroo jerky - nut-brown with a matt finish. This is a man who spends his working days under the big Cambodian sun. This is a man who at 16 marched off to fight the Khmer Rouge in the northern jungles, leaving behind school and family for a soldier’s life. In that time he mastered the weapons of war: the AK47, M16, M60 and the 37mm anti-aircraft gun (a one-year training course), before spending his final years clearing Russian and Chinese-made mines in rural lands. Never shot anyone, he says. Only a python or two. His golden tooth gleams.

Have Temple, will travel

The Golden Temple Villa, Siem Reap

The Golden Temple Villa, Siem Reap

The Golden Temple Villa lies down a sidestreet of undulating potholes and compressed detritus turned paleolithic. The hotel staff will memorise your name - they have been “programmed to receive” - but their smiles are for real and their tunics of salmon silk gleam in the subdued light of the lobby, welcoming and pleasing to weary eyes. They are all young, polite and cheeky. Room 44 comes with its own gatekeeper, "Mister Charles", a keen-eyed gecko.

Sit. Drink. Watch. Learn

Front row seats to the action, The Grand Cafe, Siem Reap

Front row seats to the action, The Grand Cafe, Siem Reap

Le Grand Cafe sits on the corner of Street 9 opposite the produce market in downtown Siem Reap. The block comprises of French-Indochine style shop houses built in the 1920-30s and whose weathered pastel facades still defy the tropical heat and damp. Cuban jazz drifts from a sound system, playing background to the passing sideshow of motorised juice carts, tuk-tuks, scooters and bicycles. A motorcycle with three passengers whizzes by; one of them holds an intravenous saline drip above his shoulders - a hospital break-and-run? Juice blenders whirr, horns beep, “watch out!” sounds in a half-dozen languages and the Cuban jazz drives on. A hot-looking local girl skims by on a black scooter with the words “Black Jack” across the wheel guard. Le Grand Cafe’s ceiling fans rotate like a chopper blades, shifting the air, pushing it out, sucking it in; the night is heavy with tamarind and promise. I reach for the handle of my Angkor beer, the colour of urine with bubbles, take a sip and toss some peanuts into my mouth just as the lights stutter, and are gone. A cheer rises across the precinct; the cafe, the street and the market are thrown into a momentary blackout; the lights return and the table banter resumes with renewed vigor.

Siem Reap, like all bustling tourist hubs, comes to life in the evenings and any restaurant or bar worth its bloody mary or fish sauce, affords a street-side view of the action. Hot greasy vapors leap from woks of the cooking mamas on Pokambor Avenue, down the road from the Grand Cafe. I pull up a plastic chair and order a fresh beer as the tourist crowds thicken. A big man in a tucked-in Hawaiian shirt blocks out my light. Picking his teeth with his little finger, he asks me the way to the Grand Cafe. That’s an easy one, but I warn him the urinals are filled with pineapple slices. Two Frenchmen pass by looking like they've marched overland from Laos, in need of clean shirts and haircuts yesterday. The side show thickens as two tattooed youngbloods with Aussie accents clutching bottles of cheap rocket juice stop to get their bearings then stagger on. Back at the Grand, a large white man with a drooping mustache pays up and leaves with a small brown woman pressed to his hip. They climb into a tuk-tuk and are lost to the night. Hmmm nothing to write home about but I begin nonetheless, “Dear Mum, they put slices of pineapple in the urinals here…” but give up and pay up. The madness elsewhere is too good to miss.

Siem Reap, like all bustling tourist hubs, comes to life in the evenings and any restaurant or bar worth its bloody mary or fish sauce, affords a street-side view of the action. Hot greasy vapors leap from woks of the cooking mamas on Pokambor Avenue, down the road from the Grand Cafe. I pull up a plastic chair and order a fresh beer as the tourist crowds thicken. A big man in a tucked-in Hawaiian shirt blocks out my light. Picking his teeth with his little finger, he asks me the way to the Grand Cafe. That’s an easy one, but I warn him the urinals are filled with pineapple slices. Two Frenchmen pass by looking like they've marched overland from Laos, in need of clean shirts and haircuts yesterday. The side show thickens as two tattooed youngbloods with Aussie accents clutching bottles of cheap rocket juice stop to get their bearings then stagger on. Back at the Grand, a large white man with a drooping mustache pays up and leaves with a small brown woman pressed to his hip. They climb into a tuk-tuk and are lost to the night. Hmmm nothing to write home about but I begin nonetheless, “Dear Mum, they put slices of pineapple in the urinals here…” but give up and pay up. The madness elsewhere is too good to miss.

5.1333° S, 119.4167° E

Drifting with Indonesia’s Master Mariners

|

“Swiftly, swiftly flew the ship,

Yet she sailed softly too: Sweetly, sweetly blew the breeze - On me alone it blew.” ― Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner UJUNG PANDANG, Indonesia. “From Sulawesi to Surabaya it takes fours days under sail, if the winds are good," says Ronnie Herawati, sweeping his bony hand across the darkening horizon. He is the captain of the Golden Star, an 85-foot-long schooner, called a prahu, and one of a hundreds-strong fleet of traditional sailing boats which ply Indonesia's archipelago. Destinations are dictated by their cargo consignments; speed depends on the prevailing trade winds and ocean currents. Herawati is of Bugis heritage - an ethnic group whose mastery of star navigation and ship-building skills is widely respected throughout Indonesia. The weather forecast for the following day is not good. But Herawati's ship will set sail nevertheless for Balikpapan on Borneo island, to swap its cargo of flour for barrels of palm oil. The ship's gaping hold accommodate 60 tons of cargo. After that, there is little space for the seamen's quarters. They must make do in a warren of airless cubby holes at the ship's stern. Above deck, the eleven crew members mill around the galley preparing a dinner of rice, grated chilli and dried fish, washed down with muddy-coloured Torajan coffee. |

Along Paotere's docks, the loading of boats is a brisk and serious business. Shipping agents wiggle in and out of rigging, checking cargo lists and counting the lorries which come and go.

Cliff Barrung, a wiry 28-year-old, is an agent with Golden Star and its sister ship, Golden Gull. "Time is money and once a boat is emptied we fill it immediately," he says, overseeing the stacking of flour bags, biscuits and bicycles, coffee beans, plastic tubing and laundry tubs, by men with blood-shot eyes and legs like tree roots. By late afternoon, Paotere's cafes fill with dockers. In one cafe, yellowing photographs of Bugis schooners line the wall and a wooden model ship takes pride of place over the cash register. Small, moon-faced Bugis sailors chat and smoke fragrant kreteks, throwing the odd glance toward the docks where boats are arriving from Timor, Flores and Kalimantan. The sky swells with thunderheads, bruised and purple. The owners of tiny warungs - street kitchens - roll down their awnings in anticipation of the downpour. Now and again a Bugis schooner leaves port, crossing the horizon with its sails strained by the warm trade winds, heading south to Timor, Surabaya, or Bali perhaps. |

6.0833° N, 116.5500° E

Mount Kinabalu, Sabah, Borneo.

SABAH, Mount Kinabalu. At Laban Rata (3,300m) the air is thinner. I walk 50m from the bunkroom to the can in lead boots. A group of Dutch tourists abandon their climb - several of their members are overcome with altitude sickness. Freezing pre-dawn temperatures, sprained ankles, headaches deter others from striking out for Low's Peak (4,095m).

My ascent starts at 3am. To rise in the cold and wet at this ungodly hour is necessary in order to reach the summit by 6am for sunrise. I fall in with a procession of 40 other climbers making their way slowly, painfully across the granite rock faces; a funeral procession of scattered lights in the chilly darkness. Guide ropes ensure no one strays to oblivion.

At 6:10am, the first rays of sunlight break over Mount Kinabalu's cold peaks. The highest mountain in Southeast Asia! To the north, Sabah's waterways snakes lazily towards the South China Sea. To the east, Kota Kinabalu shimmers under streetlights and the tiny villages of yesterday are swallowed in cloud.

Stairway to heaven for the soul, highway to hell for the knees.

My ascent starts at 3am. To rise in the cold and wet at this ungodly hour is necessary in order to reach the summit by 6am for sunrise. I fall in with a procession of 40 other climbers making their way slowly, painfully across the granite rock faces; a funeral procession of scattered lights in the chilly darkness. Guide ropes ensure no one strays to oblivion.

At 6:10am, the first rays of sunlight break over Mount Kinabalu's cold peaks. The highest mountain in Southeast Asia! To the north, Sabah's waterways snakes lazily towards the South China Sea. To the east, Kota Kinabalu shimmers under streetlights and the tiny villages of yesterday are swallowed in cloud.

Stairway to heaven for the soul, highway to hell for the knees.

13.8333° S, 171.7500° W

Western Samoa

23.7000° S, 133.8700° E

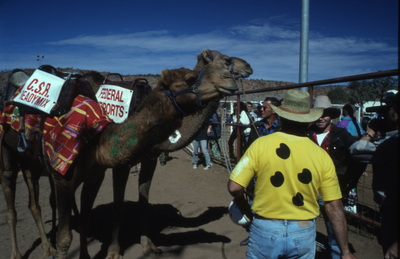

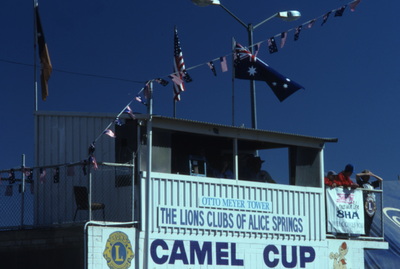

The Camel Cup in Alice Springs, Australia

“Have a drink, mate? Have a fight, mate? Have some dust and sweat, mate? There's nothing else out here.”

―Tagline to the film Wake in Fright (1971)

“Have a drink, mate? Have a fight, mate? Have some CAMEL dust and sweat, mate? There's nothing else out here.”

―Doctored tagline to the film Wake in Fright (1971)

―Tagline to the film Wake in Fright (1971)

“Have a drink, mate? Have a fight, mate? Have some CAMEL dust and sweat, mate? There's nothing else out here.”

―Doctored tagline to the film Wake in Fright (1971)

17.0000° N, 146.0000° E

Guam and Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands

Saipan teeters on the edge of the Mariana Trench — the Earth's greatest abyss. It plunges to a depth of 38,250 feet (11,582m), then rises to form a rocky knoll of mist-shrouded mountains and lush forests of strangler fig, ironwood and plumeria trees.

Ferdinand Magellan sighted the Mariana Islands in 1521, claiming Saipan for Spain and christening the archipelago “Las Islas de las Velas Latinas" (the Islands of the Latine Sails), because the sails of the native canoes reminded him of the Mediterranean fleets back home.

The island's fine coral-sand beaches and plethora of marine sports — including some spectacular WWII wreck diving — are the main attractions for tourists. For relic-hunters and war history buffs, too, Saipan is a time capsule of old Japanese command posts, forgotten airstrips and invasion beaches still littered with American tanks and bunkers.

The Marianas Visitors Bureau produces maps of World War II battle sights that pinpoint invasion beaches like those at Susupe and Chalan Kanoa, 16 miles (10 kilometers) south of the capital, Garapan, on the west coast.

It was here, on June 15, 1944, that the U.S. Operation Forager with its task force of 127,000 men, 600 ships and 2,000 planes began its sweep across the Marianas and on toward the Japanese home islands. Defending Saipan were 31,000 Japanese soldiers, holed up in caves and bunkers and ordered to repel the Americans at all costs.

For three weeks, one of the bloodiest battles of the war in the Pacific ensued, and by the time it ended on July 9, after Garapan had been taken, more than 3,500 Americans, 30,000 Japanese and countless Saipanese were dead.

Hiking along Susupe's high-tide mark, you can inspect Japanese bunkers, left now to the artistic whims of graffiti artists. Of the 68 tanks in the first U.S. invasion wave, all but three arrived safely on the beach at Susupe. According to local reports, one was swamped, another was burned, and the third one received a direct hit.

After more than 50 years in seawater, these rusting machines of war have become a more peaceful abode for hundreds of reef fish and crabs, while their intact turrets and cannons now double as race markers for jet-ski riders.

The Visitors Bureau also directs visitors to the village of San Roque and the Last Command Post, which is found in scrub at the base of the 800-foot (250-meter) cliffs on Saipan's north coast. It was here in 1944 that the Japanese commanding officer, Lieutenant General Yoshitsugo Saito, acknowledging his defeat in the face of overwhelming U.S. forces, committed hara-kiri with his ceremonial sword.

These days, tour buses swerve into a specially built parking lot, disgorging hundreds of camera-wielding tourists — mostly Japanese — to photograph the heavy guns, torpedoes and tanks that surround the post.

Others, more respectfully, pay silent tribute to the fallen soldiers at a small Shinto shrine nearby.

23.7000° S, 133.8700° E

Central Australia

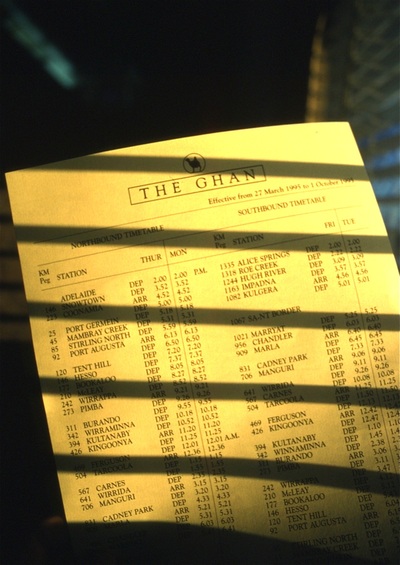

RIDING THE GHAN

DARWIN-ADELAIDE BY TRAIN: Dust storms, 50-degrees Celsius heat, floods, and having supplies airlifted to stranded trains were all part of traveling aboard the Ghan, Australia's legendary outback train, during the early 20th century. Thankfully, the big skies and red dust are all appreciated from the air-conditioned side of a tinted window these days. Named after the Afghan cameleers who supplied the early desert towns, the weekly Ghan takes two nights to make the 2,979-km haul to Adelaide from Darwin. Choose between seats, budget sleepers or luxury cabins. Read more at www.gsr.com.au.

DARWIN-ADELAIDE BY TRAIN: Dust storms, 50-degrees Celsius heat, floods, and having supplies airlifted to stranded trains were all part of traveling aboard the Ghan, Australia's legendary outback train, during the early 20th century. Thankfully, the big skies and red dust are all appreciated from the air-conditioned side of a tinted window these days. Named after the Afghan cameleers who supplied the early desert towns, the weekly Ghan takes two nights to make the 2,979-km haul to Adelaide from Darwin. Choose between seats, budget sleepers or luxury cabins. Read more at www.gsr.com.au.

9.5333° N, 138.1167° E

Yap Islands, Micronesia

The Betels and The Stones

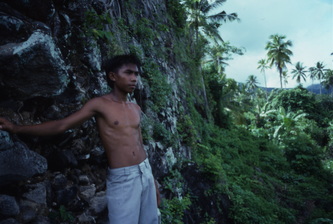

“There is nothing like a storm to make you feel closer to God," says Titus Yilus riding the clutch of his battered Nissan sedan down the jungle track towards a village called Bechiyal. Not exactly sure what my red-eyed, Camel cigarette-puffing, driver-for-a-day means by his remark, I continue to marvel at the magnificent deep purple seeping across the western Micronesian sky.

Located on the north coast of the island state of Yap, roughly 860km south-west of Guam, Bechiyal looks like the kind of place where Robinson Crusoe might have booked his holidays.

Beyond the ruffled thatched-roof huts and withered meeting houses, past the outer reef and its pulverizing swells, the horizon looks suddenly bruised and foreboding. Thousands of dragonflies fill the sky creating a crazy aerial traffic jam and the heavy smell of rain, omens easily read by Yilus, herald the end of another day of searing heat and sluggishness on this tiny Pacific island outpost.

Metres from the lagoon sits a stilt bungalow with a skinny dog standing guard. Yilus tosses me the key, lights a cigarette, ponders the heavens. “Big storm coming,” he says, jingling his car keys like a witch doctor. He disappears back up the jungle track in his sedan.

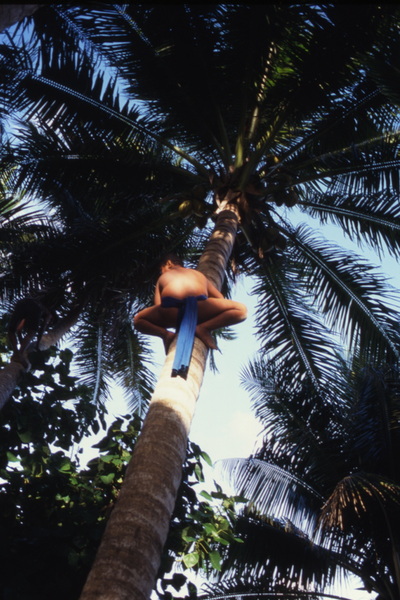

Sometime around midnight the storm breaks. Gusts of warm sea air burst through my window, inflating my mosquito net like a parachute and filling the room with a fine spray which gives everything a taste of salt. Lightning illuminates the coconut trees outside my door and thunder ripples through the timber of my hut. Burrowing deeper into my futon, a mattress no thicker than a rice cracker, I try to convince myself there is more than just a flimsy thatched roof between me and a sky charged with electrons.

“There is nothing like a storm to make you feel closer to God," says Titus Yilus riding the clutch of his battered Nissan sedan down the jungle track towards a village called Bechiyal. Not exactly sure what my red-eyed, Camel cigarette-puffing, driver-for-a-day means by his remark, I continue to marvel at the magnificent deep purple seeping across the western Micronesian sky.

Located on the north coast of the island state of Yap, roughly 860km south-west of Guam, Bechiyal looks like the kind of place where Robinson Crusoe might have booked his holidays.

Beyond the ruffled thatched-roof huts and withered meeting houses, past the outer reef and its pulverizing swells, the horizon looks suddenly bruised and foreboding. Thousands of dragonflies fill the sky creating a crazy aerial traffic jam and the heavy smell of rain, omens easily read by Yilus, herald the end of another day of searing heat and sluggishness on this tiny Pacific island outpost.

Metres from the lagoon sits a stilt bungalow with a skinny dog standing guard. Yilus tosses me the key, lights a cigarette, ponders the heavens. “Big storm coming,” he says, jingling his car keys like a witch doctor. He disappears back up the jungle track in his sedan.

Sometime around midnight the storm breaks. Gusts of warm sea air burst through my window, inflating my mosquito net like a parachute and filling the room with a fine spray which gives everything a taste of salt. Lightning illuminates the coconut trees outside my door and thunder ripples through the timber of my hut. Burrowing deeper into my futon, a mattress no thicker than a rice cracker, I try to convince myself there is more than just a flimsy thatched roof between me and a sky charged with electrons.

34.4553° N, 113.0253° E

The Songshan Shaolin Shi Decheng Wushu Centre,

Dengfeng, China

(嵩山少林释德成武馆)

Dengfeng, China: Kung Fu Diary Part I

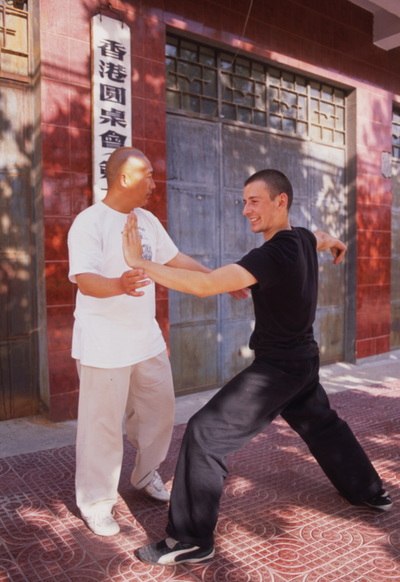

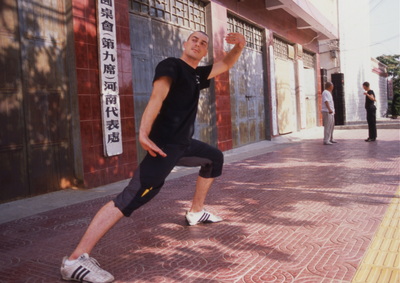

Plane trees shade the sidewalk outside the Songshan Shaolin Shi Decheng Wushu Centre. Shade. Only water is more precious in August. The shade cast by these arbors determines the length of our course each day. In the morning, when the sun is low, our path is long and hard; in the afternoon when the sun is overhead it is short and hard.

The calisthenics to build strength and flexibility make even the fittest among us discover a new muscle everyday; one each for the splitz, turkey walking, bunny hopping, cartwheeling and the hand-standing against brick walls until our faces are tomatoes ripe for the picking. Sometimes our handlers order us to shunt each other wheelbarrow-like backwards and forwards along the footpath. Occasionally, the barrow dissolves into a heap of sweating, panting, sobbing flesh -- bloodied hands our badge of honour. No-one complains.

Slowly, painfully, my limbs reach higher up the trunk of the stretching tree. The threshold of pain is being pushed back. Once taut as piano wires, my muscle fibres are now tempered rubber bands. Next follows instruction in the 18 ‘classic movements’ - chi-bun gong - the nuts and bolts of Shaolin kung fu. They seem uncomplicated at first, but their simplicity belies the excruciating pain a novice experiences to achieve strength, speed, precision and endurance. Take ma-bu, the horse riding stance: squat, legs apart, lower your centre of gravity to a fighting position and hold for three minutes until your feet lose radio contact and you are overcome with uncontrollable shaking. That is ma-bu.

Training on the street puts this suffering in the public eye. The Number 2 bus passes every 15 minutes; its bored passengers look happy to see the tall white men dancing along the sidewalk outside the school, standing upside-down against its walls, or shaking like they have malaria at a squat beneath its trees.

I don’t know the name of the street but down it the neighborhood aromas flow thickly, of savoury fried dumplings, sickly sweet chungfah (flowers), incense and some days, when the breath of the Gods is strong, Gobi sand.

Spectators come and go, watermelon vendors, garbage collectors, granddads pushing babies, all amused by the tall white tornado kickers and or the praying mantis shadows on the wall that persist until the sun begins its descent.

“Exhaustion makes the best pillow.”

It sure does. But what use is an old Indian proverb if the neighborhood pyromaniac won’t let me sleep. The wee hours resound with the kaaaBOOOM of bunkerbuster firecrackers whose echoes rattle about the Songshan mountains like loose coins in a washing machine. I guess the Gods have heard it all before, but please, Mum, send me anti-bunkerbuster ear plugs in the next aid package!

Plane trees shade the sidewalk outside the Songshan Shaolin Shi Decheng Wushu Centre. Shade. Only water is more precious in August. The shade cast by these arbors determines the length of our course each day. In the morning, when the sun is low, our path is long and hard; in the afternoon when the sun is overhead it is short and hard.

The calisthenics to build strength and flexibility make even the fittest among us discover a new muscle everyday; one each for the splitz, turkey walking, bunny hopping, cartwheeling and the hand-standing against brick walls until our faces are tomatoes ripe for the picking. Sometimes our handlers order us to shunt each other wheelbarrow-like backwards and forwards along the footpath. Occasionally, the barrow dissolves into a heap of sweating, panting, sobbing flesh -- bloodied hands our badge of honour. No-one complains.

Slowly, painfully, my limbs reach higher up the trunk of the stretching tree. The threshold of pain is being pushed back. Once taut as piano wires, my muscle fibres are now tempered rubber bands. Next follows instruction in the 18 ‘classic movements’ - chi-bun gong - the nuts and bolts of Shaolin kung fu. They seem uncomplicated at first, but their simplicity belies the excruciating pain a novice experiences to achieve strength, speed, precision and endurance. Take ma-bu, the horse riding stance: squat, legs apart, lower your centre of gravity to a fighting position and hold for three minutes until your feet lose radio contact and you are overcome with uncontrollable shaking. That is ma-bu.

Training on the street puts this suffering in the public eye. The Number 2 bus passes every 15 minutes; its bored passengers look happy to see the tall white men dancing along the sidewalk outside the school, standing upside-down against its walls, or shaking like they have malaria at a squat beneath its trees.

I don’t know the name of the street but down it the neighborhood aromas flow thickly, of savoury fried dumplings, sickly sweet chungfah (flowers), incense and some days, when the breath of the Gods is strong, Gobi sand.

Spectators come and go, watermelon vendors, garbage collectors, granddads pushing babies, all amused by the tall white tornado kickers and or the praying mantis shadows on the wall that persist until the sun begins its descent.

“Exhaustion makes the best pillow.”

It sure does. But what use is an old Indian proverb if the neighborhood pyromaniac won’t let me sleep. The wee hours resound with the kaaaBOOOM of bunkerbuster firecrackers whose echoes rattle about the Songshan mountains like loose coins in a washing machine. I guess the Gods have heard it all before, but please, Mum, send me anti-bunkerbuster ear plugs in the next aid package!

34.8167° N, 134.6833° E

The Himeji Nada Fighting Festival,

Western Japan

34.8167° N, 134.6833° E

Himeji City Racecourse

There’s this place, see, where hard-working men gather to chew the fat, throw money to the wind and curse the Gods on a Sunday. It’s no secret that the people of Himeji city, in western Japan, love festivals. Weekend horseracing is no exception. Peruse your form guide, pick your winners and pray!

35.8333° S, 137.2500° E

KANGAROO ISLAND, SOUTH AUSTRALIA

There’s this place, see, way down in South Australia, where roads are long and lonely and roamed by animalia. Lighthouses stand forlorn on bleak and rocky points, and the old men who man them all have creaky joints. But these men are brave, oh indeed they are, to weather the Roaring Forties and white pointers from afar. Who come to Kangaroo Island to feast on juicy seals (kangaroos, on the other hand, get bottle fed for meals). So come to KI where signs point far and near, letter boxes are fridges and the locals love a beer.

18.0000° S, 179.0000° E

FIJI ISLANDS

There’s this place, see, way down in the South Pacific, where your room has a sandy floor and the sea laps at your door and men hunt wild pigs with dogs and knives and “bush rugby” is played with dried coconuts and days end with a tune on a beat up guitar and the clapping sounds of kava being passed. It’s not one place, but rather a group of places --islands with names like Kadavu, Taveuni, Ovalau, Vanua Levu and Viti Levu -- where time matters not and your smile is your currency.

0.7833° N, 127.3667° E

SPICE ISLANDS

Ternate and Tidore, Indonesia

There’s this place, see, way down in Indonesia, where men smoke tobacco through clove filters and women sell red sugar, cinnamon sticks and chilies that could put a man on the moon. It’s not exactly ONE place but a group of places, islands -- the Spice Islands -- and fifteen years ago I took a ferry one night that almost nearly didn’t reach its destination. But it did. And I live to tell the story in pictures. Of two volcano islands called Ternate and Tidore. It goes something like this....