|

Moving to a new hood means having to learn the names of your neighbours. Done! (see previous blog post). It also means having to learn to write your new address in kanji and memorising the seven-digit postcode — another set of numbers to add to that sea of PINs and passwords sloshing about inside your head. Which brings me to the idiosyncratic nature of addresses in Japan. With the exception of Kyoto and Sapporo, where their city fathers actually named their streets, the rest of the archipelago still grapples with an archaic numbering system to find its way about town and city. This system can be a tough nut to crack, one that only highly-caffeinated postal workers and taxi drivers over the age of 75 seem able to decipher with ease. The call-out repairmen, pizza delivery kids, dinner guests, and most taxi drivers under the age of 75, are left to muddle through the labyrinthine streets of my hood as best they can. The only types who don’t have any problems finding me are the NHK TV subscription collectors and the nice ladies in sensible shoes from Jehovah’s Witness. Unlike in the West, where addresses are written smallest to biggest (apartment/house number, street name, town, state/prefecture/province), Japanese ones start with the prefecture in which you live, and cascade down to the number on the door of your house or apartment. Take the Royal Barber Shop (see blog post: ‘Life on the Razor’s Edge’) which lies across the rice paddy at the end of my street. Its address is: Hyogo-ken, Himeji-shi, 2 Chome-10-24. This means that the shop is located on the 24th lot (of land), in the tenth block, of the second neighbourhood in the town of Kitahirano, in the city of Himeji, Hyogo prefecture, Japan. Now imagine there are apartments above this shop, and that you live in #103; then your address becomes 2-10-24-103. You are almost an ISBN. But what makes the address of the Royal Barber Shop so much easier to find is that it includes the town name — Kitahirano. Many old towns (machi) have been absorbed into the ever expanding city (shi) of Himeji, and while on a map they resemble suburbs, at ground level they’re still a thriving, noisy cluster of shops, houses and rice paddies squeezed between schools, temples and shrines, with a clutch of restaurants and bars, a barber, a bicycle repair shop, and a convenience store. A machi is much easier to find. So, you now know that the Royal Barber Shop is located in the town of Kitahirano — but where exactly? The street on which it sits has no name or number. Google Maps will pinpoint the neighbourhood (chome) and give you the block (banchi), but it won’t reveal the number (go) of this exact location. This is because residences and businesses rise and fall, year after year, old for new, dividing and subdividing and so on. The streetscape may change, but the banchi rarely does. In which case, a very commonsensical approach works wonders: the use of landmarks. I would tell it like this: “Get the number 3 bus from Himeji Station to Kitahirano. Get off at the Inoue Cake Shop, walk past the Feinkost butchery, past the 7-Eleven and the Windsor Tea House. You’ll find the Royal Barber Shop on the left-hand side, just before the Sumigo izakaya. Ask for Tada-san, the big guy with the gap-tooth and calloused knuckles. He gives the closest shave. Closed Mondays.” Call the address system sophisticated, can call it ancient, call it head-banging and neuron-numbing even. I just call it the way to my home. Life on the Razor's Edge: https://www.mightytales.net/seaweed-salad-days/notes-from-himeji-japan-life-on-the-razors-edge

0 Comments

|

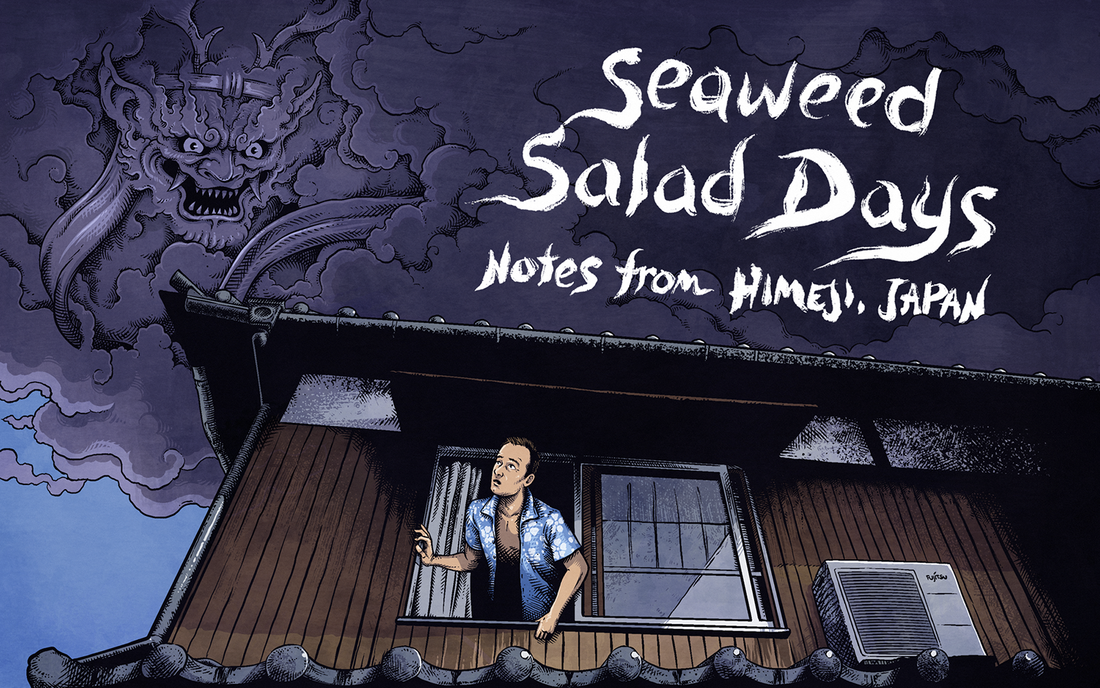

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed