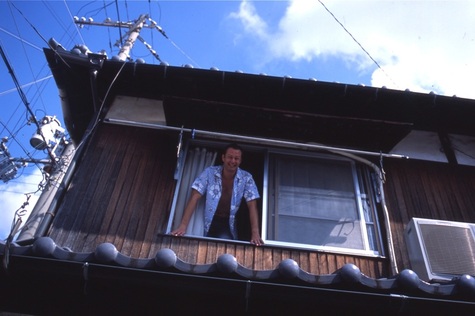

Train on the Kakogawa line Train on the Kakogawa line What do commuters think about on their long rides to and from the mills each day? I bet they don’t think about how lucky they are that the wheel was invented. I was a commuter once - a nameless man in a salt-stained suit and headphones. A Business English instructor, a corporate gun-for-hire with a bandolier of Ballpoints (™), a ronin who could commit hara-kiri with the edge of a Let’sTalk2 cd. But didn’t. Because it was never about the destination - the depressing chemical plants, semiconductor factories and sinister steel mills waiting for me at the end of the line - it was about getting there. The Kakogawa line train is the quintessential ‘paddy lands express.’ Four years of rattle and roll through the greenest rice fields this side of the Japan Alps, from the Seto seabord to the lush hinterlands of Hyogo, a place where frog eats fly and snake eats frog and snake gets beaten to a pulp by village boy. The journey (like the boy) neutralised the destination. The Kakogawa-sen follows a great, slow-moving torrent called the Kako River. If you've ever seen Apocalypse Now or read Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, for four years that guy in the story (Willard in the movie, Marlow in the book), that was me. I wish I could say I found someone as interesting as Kurtz at the end of the line, but alas, there was no badass. The two-car ‘conductorless' train still departs Kakogawa station at 20 minute intervals, bound for upcountry with students, workers, Guinness Book grandmas and sometimes a foreigner or two. Young women still sleep on the shoulders of strangers and college girls still doze and nod their heads like glam-rock groupies as the train bounces down the rails. Some days the entire car looks like it has been gassed; passengers everywhere, draped on each other, slouching, snoring. I stepped over a fat boy asleep on his back on the aisle floor once. My destination was Yashiro, a place where trains pass hourly and the station attendant is a large, fat ginger cat which eyes passengers suspiciously as they pass through the turnstile. In summer, midge flies, moths and nymphs cloud the platform. Fuzzy caterpillars crawl over the bench seats and spiders abseil from the rafters. In winter they disappear and the soft, silent misery of falling snowflakes fills the hour-long wait for the night train back to modern-day Japan. I don't miss the long commutes. But I do miss the man who was always waiting for me at the end of the line. A taxi driver named Yamamoto. His shiny black Nissan Cedric always got me to the mill on time. Love him or loathe him, I still can't decide; he was both the endearing face of small town Japan and the Mister McGoo of public transportation. He drove at a speed I could have bettered running on my knees. He clocked 39 km/hr once on a paddy by-pass. He would veer and drift all over the road, squinting over the wheel as he squeezed out his best radio-learned English. He once answered the dispatcher in English: “Oooh yes? How are you today? I am very fine, veeeeeery fine thank, and you? Hahaha-ha!" Every conversation with him ended the same way: “Many thankyous Mister Simon, for the free English lesson."  Rural Hyogo - the unending experience Rural Hyogo - the unending experience

2 Comments

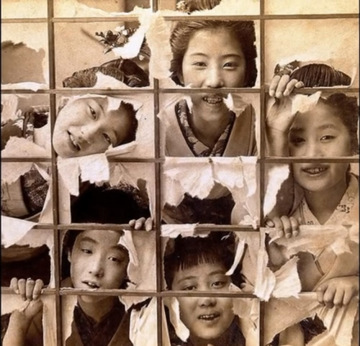

What my papers doors look like now. What my papers doors look like now. “Nothing lasts forever. Not even a rock,” says Kawabata-san, pouring two glasses of beer. He slides one across the table. “To your long life.” Kawabata-san runs the liquor store on the old shopping street near my house. It stands next to the butcher, opposite the yakitori grill, across from the tea ceremony teacher’s house. It has a vending machine outside and the rumble-and-THUNK of bottled beer falling into its hopper is a familiar note in a symphony that fills this street at the end of the day. Coins tumble, bottles rumble, liquor loosens tongues, lubricates conversation, firms up trust and builds friendships - it’s the glue in the social fabric of communities all over Japan and in the Good Hood of Himeji city, too. And so passes an afternoon of drinking and philosophising in the backroom of a liquor store, about the demise of the old neighborhood in which we live, and all the while the outside traffic heads north away from the city, the school kids in new uniforms marching by in scattered ranks, Mitsubishi Electric workers cycling home under greasy collars, ancients walking their dogs to nowhere in particular. The city winds down, the bathhouses fill up and dinners are served, beer bottle caps lopped off and TVs revved up. Another day gone. Kawabata-san burps. “Nothing lasts forever.”  What my paper doors used to look like. What my paper doors used to look like. For 15 years I’ve borne witness to the slow demise of a traditional neighborhood, the old houses being pulled down to make way for tax-effective car parks and smaller, more compact houses built of shiny, weather-resistant materials that make them look like cheap toys from Guangdong. “Many see old not as ‘classic’ but as unfashionable and inefficient,” Kawabata-san says, refilling our glasses. “The traditional Japanese townhouse is too hot in summer, too cold in winter, too dark, too airy, too noisy in typhoons, too quiet when it snows, too hard to maintain. Me, I love mine!” And me, mine. Yet, as new houses rise around us, I ponder the fate of my 100-year-old mudwall-and-tile abode, built in 1916 by the hands of master craftsmen. From the street it looks haunted. There’s a ‘pissing pole’ for local mutts outside, a crapping gallery for the crows in the power lines overhead, and twice a week, residents deposit their garbage bags (neatly) for collection along my south wall. I can replicate the roar-and-chomp of the midnight garbage truck perfectly. Ask me next time. I have come to favour its weather beaten facade, coarse tatami mats, creaking stairway and winter sunlight which streams through the holes in the paper doors. It's the tilt that worries me. A ping pong ball rolls across the floor from north to south at speeds which grow faster each year. Maybe it's time to join the slow bleed of the Good Hood and leave... I repapered the shoji sliding doors the other day, and the fusuma paper doors, and the amido fly screen netting that flapped against the window all winter. These are jobs designed to give you gorilla knuckles and a Quasimodo stance. I won’t miss them. One day this house will crumble and return to the earth, or to the Matsui Demolition Company which will bring in their ‘Komatsu Claw’ - a tracked house-munching machine that rips and shreds for a living. I will have to search the world wide web for a new dwelling, and a new ‘Good Hood.’ “Nothing lasts forever,” Kawabata-san says, looking at our empty beer bottle. The mountains behind Himeji look promising; cooler in summer with a view of the sweltering sprawl and glowing metallic centipede we call the shinkansen that passes through the city. Wherever I hang my hat in the those mountains, I will take pleasure in rolling the ping pong ball one last time. From the top of my street. Next week: The writer takes Himeji's Train to Nowhere. |

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed