|

From late June to mid-September, we of the Good Hood drink the air not breathe it. The humidity is crushing and life becomes strangely aquatic as we wallow in a bath of our own making and watch our skin take on a shiny, glistening sheen.

The elderly tend their gardens at sunrise to beat the heat, eat watermelon, then burrow away in their dark, ancient houses until it subsides. Then, around sunset when the lights come on, windows open to reveal elderly men stripped to the waist with cold bottles of beer and televised baseball games turned to full volume in front of them. These--and eating more watermelon--are the rituals of summer in the Good Hood. Another is bathing regularly. “A shower twice a day keeps evil spirits away,” says my old friend Ono-san. By “spirits” I think she means the odorous kind. Whatever. It doesn’t stop a crust of salt forming on my hard-working collar. If you’ve been following this blog, you will note that kids don’t feature much in the Good Hood commentary. This is because, like water sprites, they seem only to appear on weekends along my neighborhood river, the Semba, where the medaka fishing is good. That is until summer holidays begin. Then hell breaks loose, an amiable hell, punctuated by the whump! of a soccer ball against the neighbor’s wall or the pop-pop of a distance skyrocket. And suddenly sprites are everywhere. But what really signals the start of summer is the 6:30am reveille, the call to arms (and legs and stiff torsos) by NHK national radio and neighborhood associations across Japan. This is “rajio taiso” (radio exercises), a tradition designed to raise the nation’s youth at ‘school hours’ throughout their summer holidays. In my neighborhood, where many residents have been up since 4am, the crackle of the NHK broadcast from a portable radio is matched by the crackling of knee and hip joints as the elderly lead the sleepy-eyed youth in a gymnastic routine in our local park each morning. So where to cool off as day wears on and humidity climbs? The Funabiki Mens’ Barber Shop is a good start; it’s air-conditioned for your comfort, with Tahitian Lime hair tonic to cool your scalp, piped Okinawan music your temper and the rhythmic snip-snip of scissors to lull you into a perfumed doze--until the perfumed bill arrives. For the kids and the elderly life is just one big sweet watermelon. But what about the poor parents of the Good Hood? How do they keep their cool during the long hot summer? I know the answer because I have served on the neighborhood rubbish collection supervisory team (NRCST) and twice a month, at our designated collection point, have watched the middens of empty beer cans rise to rival the Pyramids of Giza (well almost). Speaking of liquid refreshments, next week’s blog squeezes into swimwear and goes to the City Swimming Pool. Stay tuned.

0 Comments

When the residents of the Good Hood roll out their futons and fluff their chaff pillows at the end of another long, sultry day, most are too tired to hear the orchestra warming up outside their window: the clicks and whirrs, hisses and purrs, croaks and growls of the neighborhood’s other denizens.

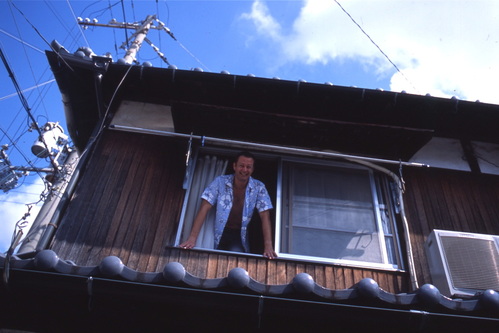

The ‘others’ are the insects, reptiles, stray cats, pets-on-the-run, drunk English teachers and other nocturnal animalia exotica that take care of their primal needs after the meek, the sane and the sensible have hit the tatami mats. Like other towns and cities across Japan, Himeji’s skies, streets and waterways crawl with creatures of the scaly, slimy, boggled-eyed or beaked kind. Look into the sky on sunset and you’ll see hundreds of black crows cruising north after scavenging the city streets and parks. Where are they headed? “Where do you think,” says Smokin’ Joe Masumoto, the old kitchen gardener who lives up my street. “The Crow Bar. Ha-ha!” (Is the quality of one’s jokes relative to one’s age? Chew on that one and get back to me.) But back to the animals - ah yes, the bats that skirt and dive for insects over the Semba River on dusk, the white egrets that trawl the shallows for medaka fish, the swallows that roost under the eves of people’s houses and bother no-one. Unlike those damn paddy frogs. How would you like a million amphibians on your doorstep, generating a sonic ripple that comes in nauseous waves from across the rice paddies? If you live close enough, your money is on the paddy snakes. As this traditional neighbourhood declines as a result of an aging population and a preference for modern building materials over traditional ones, an irony emerges. Nature is making a comeback. Yesterday I passed by a clump of ivy in the shape of a house. A few doors down stood a residence taken prisoner by bamboo gone mad. Roots have penetrated its entire block, pushing spears through the roof and encaging the house in a green grill. Nothing has come or gone from that place, to my knowledge, for ten years. The gardens of these abandoned homes run wild; they become a fruit free-for-all, a biwa (loquat) bonanza, a persimmon party, kinkan (kumquat) and kiwi klatsch for the local birdlife. For months I could not locate the source of a mysterious pinging sound outside my toilet window. Then one day I looked up and there, balanced on a telephone wire, sat a fat crow firing persimmon seeds out its butt at the drain pipe. Dink, dink! ping-padink! Now late July and the incessant drone of cicadas heralds the end of the rainy season and onslaught of summer. Can you imagine the sound of a food processor filled will one yen coins, turned on ‘high’. Multiply that din by ten and you’ll appreciate what I’ll be waking to over the next six weeks. Ah summer. Now there’s a season to test the best of the Good Hood. But more on keeping one’s cool next week.  Last week I told YOU about the smells of the Good Hood, the crazy potpourri of soy sauce, Tahitian Lime hair tonic, rice paddy water, dog piss and yakitori smoke that defines the traditional neighborhood where I live. My house does not contribute to this because noise generation is our speciality: kids screaming, meal pots clanging, bath toys ricocheting, shouts, screams, whistles, mixed with the sounds of Marvin Gaye and my six-year-old singing Jingle Bells. Just what goes on inside The Foreigner’s house? My elderly neighbors can hardly imagine. But let me talk about the building itself which contains this madness. It’s a traditional Japanese town house made of wood, bamboo, mud and heavy kiln-fired roof tiles, built in the year of Meiji Emperor’s death, 101 years ago, and my home for the past 14 years. It rises two stories, with tatami rooms on each floor and paper doors dividing them. There are also tokonoma alcoves for hanging scrolls and psychedelic crayoned Father’s Day portraits. Few buildings of its likeness still stand in the Good Hood. Many have fallen to the wrecking ball, only to have risen again as high-tech ‘earthquake-proof’ homes with all-weather exteriors and fake wooden floors which hum with robot vacuum cleaners and plasma screen walls. Such homes you must grow into. Traditional Japanese houses, on the other hand, grow on you; and I’m not talking mold either. It’s not the creaking stairway or the earthen walls which shudder in typhoons, or the paper sliding doors which rattle like old bones in earthquakes, or the hidden gaps in the tatami mats which offer a revolving door service for insects great and small. No, it’s more simple than that; it’s the natural materials and the atmosphere they create. The smell of tatami, the smoothness of the tokonoma wood, the diffusion of light through paper doors and the shifting breeze about the engawa (veranda) that Japanese like my old friend Ono-san appreciate. She says traditional mud walls breathe better than plasterboard and to never underestimate the strength of natural wood beams in an earthquake. With each year passing year, however, each typhoon and long hot summer, a little more of this house returns to the earth and the air and a little more energy and ingenuity must be expended to keep it inhabitable; I corked the walls with my socks during the last typhoon and re-papered the sliding doors with ‘plastic paper’ to stop my son from punching them out. But there are some tides that can’t be turned, like the ping-pong ball which rolls smoothly from east to west without any coaxing, indicating the house has a serious lean. Unlike me, it’s on the move. A final word on the non-human inhabitants. A gecko stands guard over the front door at nights, goes by the handle, Ralphie. Mosquitoes that give him the slip are dealt a heavy hand by us humans. The white ants have been driven off, the slugs banished and the insect world now favours the arachnids--enormous yoru-gumo spiders which roam the tatami on hot summer nights. We call them the Roach Rangers. Before I forget, some years ago two English teachers who lived in this very house discovered a snake in their squat toilet. At first they were suspicious and looked at eachother accusingly, but realising it was alive, quickly photographed it for the record and dispatched it with jerk of a flush chain. Like many newcomers to the Good Hood, it’s easy to take a wrong turn and get yourself lost. Let’s keep with the animalia topic. Next week: The Good Hood Runs Wild. A few years back, an elderly woman passed away in my neighborhood. I didn’t know her name but I used to see her in calligraphy class each week at the community centre where I taught English. The ambulance staff wheeled her away on a gurney and left her house to stand empty for two years. Then two weeks ago the Machines moved in. Where she once cooked, ate, slept and tended her chrysanthemums, the smell of a freshly-poured carpark now lingers. When a house made of mud and bamboo walls, tiled roof and tatami floors falls to the Machines, it leaves an olfactoric imprint, a strange mix of ancient carpentry, clay, straw and horse hair, that is hard to forget. “Nothing lasts forever,” says my old friend, Ono-san. “Not even a rock.” Not even the 100-year-old townhouse in which I’ve lived for the past 14 years. A few more years please! But life in a declining traditional Japanese neighborhood rolls on, yes it does. Crowding the air with its odors, scents, aromas and fragrances--a whiff here, a waft there--smells that define the weather and seasons, daily rituals, festivals, people’s homes and businesses. Can YOU define your neighborhood in smells? In 500 words I’m gonna try... ...or at least you are. Go ahead, see if you can match the smells to their sources opposite:

And there are many others. When a southerly blows up my street, there’s a hint of Tahitian Lime hair tonic from the Funabiki Men’s Barber Shop in the air; a northerly brings the smell of camellia oil and the promise of a big hair day at the Wella Ladies Hair Salon a few doors down.

Smell the seasons, too: the heavy pungence of rainy season (now), the tang of altar incense in Obon (Aug), the sweet scent of kinmokusei flowers (early Oct) and the bitter smell of burning chaff after the rice harvest (late Oct). Can’t wind this post up without mentioning the curious cocktail of smells which resides in my own house. Something like this: add one room of damp paperbacks to three rooms of tatami mats, soak in sweat for one long hot summer, drizzle with soy sauce and garnish with empty beer cans. But more about the grand old Japanese house I live in next week. Answers: 1i. 2g. 3h. 4e. 5j. 6.f 7.c 8b. 9a. 10d. |

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed