Sacred and very expensive. Simon Rowe. Sacred and very expensive. Simon Rowe. Rolling thunder? Hunger pains? Another murmur from the Yamasaki fault line? No, that deep rumbling sound which fills the night sky over the Good Hood is the sound of a festival brewing. The beat of the taiko drum heralds the approach of another year’s worth of shoulder pain, chanting, sweating, drinking and more drinking, all crammed into one day in October. There’s not a moment in the Himeji city when I feel closer to the soul of Japan than at matsuri (festival) time. When the smell of burning rice chaff signals the end of the rice harvest and the sickly sweet aroma of the kinmokusei flower fills every street, lane and alley. Matsuri! Matsuri! The sound of drums can be sourced to the backyard of my Jichikai-cho, the neighborhood Boss, and our elaborately decorated centrepiece, the omikoshi, or portable Shinto shrine. Generating the thunder are the small arms of the neighborhood school kids. Two weeks before festival day, they hammer volleys into the night sky, honing their skills, perfecting their rhythm for the big day. One day before the festival, the Boss summons me. An extra pair of hands is needed to assemble the omikoshi; it’s an intricate and fiddly job which entails bolting, knot-tying, binding the shrine and attaching ornaments to its housing. When preparations are complete, six packs are passed. Quiet slurping and furtive glances towards the sky follow. Will Raijin the God of Thunder stay away tomorrow? Across the archipelago, autumn festivals are thrown to honour the Shinto gods and give thanks for the rice harvest. But as my good friend Ono-san laments, it’s a meaning too often drowned in drinking, eating, macho posturing and the excitement of carrying the omikoshi. I reply: “And you think Christmas is just the Big Man’s birthday?” The night before the festival, our illuminated omikoshi ventures into the streets swarming with school kids and pushed and pulled by fathers who have escaped the office early. Lanterns hang from residents’ porches like overweight glow worms. The omikoshi moves slowly, like a dinner cruise boat along darkened laneways.  The Tiger of the Good Hood. Simon Rowe. The Tiger of the Good Hood. Simon Rowe. Festival day breaks with a clear crisp dawn. I don my blue festival jacket with its giant red kanji character for “festival” on the back, shake the night’s hangover from my head and secure by self-pity with a red bandanna. The Boss gives a speech. Cups of sake are passed. Died squid jerky, too. A staccato drum beat sends the men to the yokes and together we carry the omikoshi to the local shrine to be blessed by the Shinto priest. Joining us are other neighborhoods, their omikoshi topped with dancing lions and decorated with tigers and bamboo, each supported by an entourage of mothers, wives, kids, babies in prams and the occasional lost tourist. The day wears on, the sun beats down, bento and beer flow, and through the Good Hood the omikoshi rumbles and rattles like an old war horse. The sound of its drum brings residents to their doors bearing envelopes of gift money. For this they receive a boisterous, semi-drunken chant and vigorous shaking of the shrine by its bearers. Rice millers, tatami weavers, barbers, tea shop and restaurant staff come out of their shops to cheer us on. To a destination I’m no longer sure of, or even care. The omikoshi becomes a lifeboat for those who have drunk too much. Stay with us! Don’t let go! The taiko beat feels like a huge rolling rock inside of our heads. By late afternoon the chanting eases, the fall of the drumstick dependent more on gravity than energy, the bearers are tired, the drummers slightly deaf and the mothers’ auxiliary strung out in the streets behind us; only the babies waking from their afternoon sleep are punching the air. On sunset, as the crows fly north overhead, we give thanks for another great day, then set to work dismantling and packing away the omikoshi for another year. Once the roller door is pulled shut, I turn and head for home, bone weary and beat. The Boss summons me. I cringe and turn slowly to face my fate: the other annual tradition in the Good Hood I forgot to tell you about -- the matsuri AFTER PARTY!

0 Comments

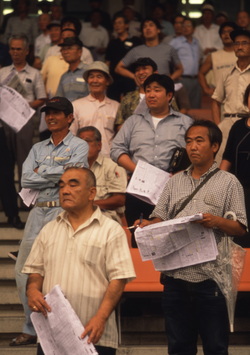

Sunday morning, what to do, what to do? I could tune in to the gossip from the Wella Ladies Hair Salon up the street --Mr so-and-so got drunk and peed on Mrs so-and-so’s hydrangeas again -- or I could tune out in the Himeji Castle park with some cold beer and dried squid and make animals out of the Autumn clouds. Or, I could go to the horseraces! The Japan Cup it isn’t but the sights, sounds and smells of a day at the Himeji Racecourse have a gritty charm of their own. Call it a polyester parade, a high-tar heaven for the hard-working men of this great city who pay their dues from Monday to Friday in the steel foundries and heavy fabrication plants along the coast. Sunday is their day. That they blow their sake allowance on horses with names like Storm Mouse, Milky Magic, Long Camelot and Special Aroma is beside the point. It’s the thrill they come for. Unlike in the West, horseracing in Japan is the ‘poor man’s pleasure.’ There are no fine dining facilities, no millinery or manners on show. Admission is 100 yen, the concourse is crowded, the green tea dispenser overworked and the betting hall haze heavier than a Jimi Hendrix riff. Despite this, a festive atmosphere prevails. My mate Smokin’ Joe Matsumoto, the kitchen gardener who lives up my street, first visited the race course as a ten-year-old in 1956. “Back then the track was a ribbon of dirt and the starting gate a piece of rope,” he says. “Horses that bolted before the Marshall’s call threw their jockeys over it.” At big city race courses, fortune-tellers, called yosoya-san, sometimes set shop up outside the front gates. For 300 yen (a few bucks) per race, they advise the punter on which horse to back based on his zodiac sign blood type etc. To my knowledge, the only thing predictable about these people is the high speed at which they move on if your horse doesn’t come in. I trust in my own good sense as the contenders for Race Eight enter the paddock. A flighty beast bearing the number “six” enters last and I crack a smile when I see this one answers to the name “Shrink.” The purse for Race Eight is a handsome 900,000 yen and excitement builds to fever pitch on the concourse overlooking the paddock. A tooting trumpet sounds the start of the race. No sooner does the last horse (I might have guessed) -- Shrink -- enter the starting gates then they’re off, bolting through a spray of hot sand. In each punter’s mind only 1400 metres separates him from his winnings. And like them, nothing I feel is coming between me and a fist full of “Souseki’s” (1000-yen bills) that my horse, Buzz My Heart, will bring home today. But something does. Through the dusty haze the pack falls away one by one, two by two, until on the home stretch there is only one horse out front. The winner by five unbelievable lengths. Number Six. Shrink. Next week: The Good Hood goes to the Nada Fighting Festival!

|

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed