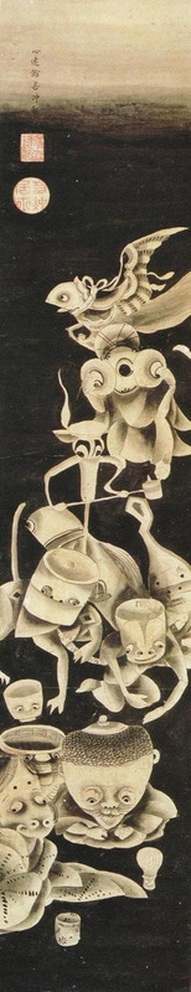

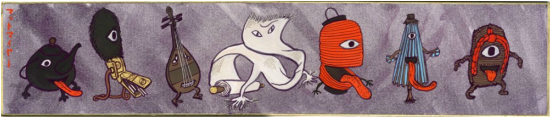

"Tsukumogami no tzu" by Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800) "Tsukumogami no tzu" by Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800) Stands to reason that in tough economic times, people spend less on luxuries and more on small pleasures - like beer, cigarettes and Uniqlo underwear. A new rooftop beer garden opened in Himeji last week (two floors above Uniqlo), affording more skyline drinking space for the hard-working denizens of this town; another place for them to catch a cooling Inland Sea breeze, run their snouts through the all-you-can-eat buffet troughs and drink whatever it takes to forget those tough economic times ahead. When will they end? They may never end. The bean counters in Tokyo would like them to end because people who don’t spend keep prices down, which keeps salaries down, which forces retailers to cancel each other out in fight-to-the-death discounting wars. But you can read all about that in the papers. There is another, less sophisticated way to measure consumer spending in this country. It goes like this: twice a month, usually at dawn, in villages and towns and cities across the archipelago, Japanese shuffle to a designated spot - a street corner or carpark - and toss out their unwanted household goods. This purging of solid waste, called sodai-gomi or “BIG rubbish,” is both a barometer of economic ‘health' and a measure of excess. Let me explain: Back in the Bubble period of the 1980s, materialism went berserk; big companies issued juicy bonuses twice (sometimes thrice) yearly to their workers and a newly-arrived foreigner with zip to his name could furnish his home with two or three trips to sodai-gomi collection point. The pickings were fat: Onkyo stereo systems, Panasonic vacuum cleaners, Toshiba refrigerators, heated tables, snowboards, scuba diving gear, pachinko machines, suitcases filled with dildos (sighted) - many of them abandoned for no fault of their own other than they had ‘lost their sheen.' The ghosts of those ‘gaijin gomi hunters' still haunt the late night and early morning junk piles, or what little there is of them. See, now that company bonuses are down, only really boro-boro household appliances are released from servitude. Which leaves the professional scrap metal collectors to fight over the greasy microwaves, bent futon poles, cracked coffee makers and wheezing electric fans. It's a solemn species of man who does this job. I pulled my sodai-gomi duty last week. By some weird design, I was paired with Smokin’ Joe Matsumoto, my friend the old kitchen gardener who lives down the street. For three times a year we get to play Big Kahunas of the junk heap, greeting our neighbors, helping them with their empty beer cans, bottles and newspapers, reaping news of who has died, gotten married, gotten divorced or gotten a hip replacement, and generally facilitating this ‘bush telegraph' until 8am arrives and we split for coffee and cigarettes. Some observations: low-malt (cheap) beer consumption is up, so is cheap Chilean red wine, sake is down, newspaper readers are down, too. In fact, year on year, the size of our trash heaps grows smaller. Blame it on a languishing economy? Or maybe a disappearing neighborhood? “Old people think old. If it's not broken, they don't throw it away. If it is, they mend it," says Smokin Joe. He lights up, puffing thoughtfully. “A lot of elderly still believe in “Tsukumogami," the ‘Gods of Useless Things.' They believe that when a tool or a container or a piece of kitchenware reaches the 100th year of its working life, it receives a soul. And that must be respected.” Tsukumogami belong to the yokai world of Japanese ghosts, goblins and other mythical trouble-makers, and while they're generally harmless, they can be mischievous, says Smokin. “They can take revenge on owners who are wasteful or thoughtless." Days later, in the cool depths of the Himeji Museum Library, I found an example of the Tsukumogami yokai: the Boroboroton, or possessed futon. It warned against leaving your futon out in the rain, eating food or spilling drink on it, forgetting to air it and clean it, for one dark stormy night it will rise up, toss you out, entwine itself about your head and neck and strangle your worthless, lazy bones! The caption beneath this horrifically graphic depiction in the book read, “A Boroboroton will come to life when feeling ignored or needless." Fair enough. Other potential mutineers in your household are the Kameosa (possessed sake jar), the Zorigami (possessed clock) or the Ichiren-bozu (animated prayer beads). And may the Gods of Useless Things have mercy on your soul should you do wrong by your Yamaoroshi; couldn't think of anything messier than a fight with a possessed radish grater. Ouch.

2 Comments

|

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed