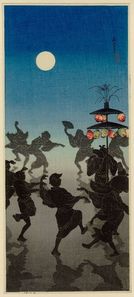

Bon-odori woodblock print byTakahashi Shotei Bon-odori woodblock print byTakahashi Shotei Beebedy-beep-beep~ Air traffic over Japan will be heavier than usual this Saturday night. Across the archipelago, over city, town, village and paddy, spirits of all ancestors will return en masse to the Earthly world. Obon will be a blast (for them): three days of lurking and lingering in incense-filled rooms, with the pinging and bonging of altar chimes and the hum and drone of the visiting Buddhist priest’s sutras to venerate and refresh their retired (and tired) souls. In addition, the living must leave their cool, dark homes and venture out under a blistering August sun to pay further homage. This means, for my old friend Ono-san and my old kitchen gardener mate Smokin’ Joe Matsumoto, a trip to the cemetery. City of the Dead, Spirit Suburbia, Hallowed Heights - call it what you will, but here in Himeji city, Ono-san, Matsumoto-san and half a million more know it as Nagoyama: an entire hillside combed in long, neat rows of gravestones which rise to a Buddhist stupa at the summit. From here I would like to say that ‘on a clear day you can see forever’ but the mills of Nippon Steel on coast cause me to swallow my words. Small paper lanterns are lit and placed at the graves on the first day of Obon to ‘guide’ the spirits in - much like the runway lights of Kansai International Airport. Gravestones are then wetted and cooled with ladles of water and rubbed off, their are chrysanthemums changed, offerings made, incense burned and prayers murmured.  Party in Good Hood. Onatsu-Seijiro Festival, Himeji. Party in Good Hood. Onatsu-Seijiro Festival, Himeji. Occasionally a hard-up drifter might take liberties with the offerings of fruit, snacks and cans of beer and sake, there’s no law against it, but you won’t catch me peeling hot oranges and drinking boiling beer reserved for the spirits. Obon is a strangely eerie time. Cicadas fall out of the sky dead, crisp as beer snacks, the streets and alleys of the Good Hood, my home for 18 years, are suddenly lifeless, dreary even. Thankfully, Obon is sandwiched by vibrant summer festivals - in the weeks before and after, fireworks turn the nights into day and Himeji’s neighborhood streets fill with stalls and parades of dancing women in yukatas. And the Good Hood, despite its slow decline, partakes. Lanterns are hoisted high on the shopping street, yakitori and cotton candy stalls materialise and the courtyard of Keiun-ji Buddhist temple glows with candles and the cheeks of old shakuhachi flute players who have over-imbibed on beer. Children appear in yukata, followed by parents and hobbling parents’ parents, all eager to sample the night’s delights; for the kids, that’s mountains of coloured ice and for parents, an icy Kirin lager will do nicely thankyou. Obon also means the return to hometowns of old school friends, which in turn means you will be hard-pressed to get a table at any of the city’s burgeoning rooftop beer gardens around this time because of all the sodden reunioning. Seaside Japan empties too after Obon; kids suddenly remember the mountains of summer holiday homework they haven’t touched, while company workers trudge drearily off to catch a bus to somewhere they’d rather forget, dreaming instead of the past week’s seafood feasts, bikini girls and white caps of the Japan Sea or Pacific Ocean. And just like that, summer will have gone, slipped through our fingers. Melted away like a wily ancestral spirit.

2 Comments

Flat as a teppanyaki grill this city of half a million might be, but in August it’s nigh as hot as one too. You know it’s hot when Fujimoto-san, the coolest cucumber AND the hardest working noodle chef on Otemae Street starts sweating into his dough. A little salt to taste? All good in this summer swelter, I say.

Horsepower beats pedal power in August. So, in a country where small is king, I will join the perambulating proletariat in compact, air-conned comfort. I call mine the “Little Red Rocket” (a Polo Volkswagen) on account of its candy apple red paint job, and “Little Red Heartbreak" on account of the money I have since paid for it in repairs. Still, it's the bee's knees for negotiating the labyrinthine network of streets over which Himeji sprawls and if this city were indeed a human body, with Himeji Castle the beating heart, I would live at the end of one crooked capillary, a street not widened since the last rickshaw drag race in 1901. There is no need for traffic lights here in the Good Hood - you simply cannot drive faster than a centegenarian doing a soft-shoe shuffle to the convenience store. And this is no place for goading six cylinders either - a Zen state of mind prevails, people motor about like they’re listening to the “Sounds of One Hand Clapping” or “Haiku Hits and Memories.” Even in August when you’d expect tempers to rise with the mercury, they don’t. Drivers nod and bow to each other, slowing to allow pedestrians to cross where there are no crossings, giving way when there is no legal (or rational) need, and allowing fellow motorists to edge into long traffic streams ahead of them for no good reason other than goodwill. Which is not to say that Himeji is driving Heaven. Hell, no! My facial muscles grip my skull each time I venture beyond the comfort zone of the Good Hood where I’ve lived for the past 18 years. An instructor at the Sanyo driving school where I took a refresher course years ago warned me. He said, “Himeji drivers are the second-worst in Japan.” “And the worst?" I squeaked. “Osaka,” he said, clicking his tongue and looking towards the east. “Fuhgeddaboudit.” I concede, some drivers a little too Zen in the head here. Zen-drunk even, when empty mind is overtaken by absent mind. There are drivers who park on sidewalks, leave engines running outside 7-Eleven while they do their shopping, run red lights, juggle dogs and babies and cell phones, and on the sight of any orange traffic light, they put the pedal to the metal. In Himeji, 10km/ph over the speed limit is deemed acceptable. You could go drive slower of course, but only the cops do that, which lends them an air of ominousness which I suspect they like. Civil servants with power exert it - even if driving a desk. I sat through a mandatory lecture at the Himeji Police Station, filled with the yawning and the young, grinding my teeth as the traffic wardens ran through the car accident statistics for the previous year. The atmosphere would have made an actuaries’ conference look like the last party on Earth. And the people who really should be there? The yakuza? No. The bōsōzoku (暴走族, literally “running-out-of-control tribe") motorbike gangs? No. The geriatric red-light-runners? No. In my mind, the greatest threat to humanity on the streets of Himeji is the 'young momma', the woman who is five minutes late for her son’s piano lesson. At her disposal is 2,500 ccs of hot-greased Japanese technical know-how, satellite-connected, TV-equipped, iced latte-filled and antsy-fumed. As a cyclist, I have been cut off at corners, edged into azaleas, brushed at signals and generally looked down upon from the captain’s chairs of these hot-greased family wagons all my life by these women. But not today, no sir. I’m looking up. Looking up from the air-conditioned comfort of my Little Red Heartbreak with The Police on full volume, singing “De Do Do Do, De Dah Dah Dah is all I want to say to you!" |

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed