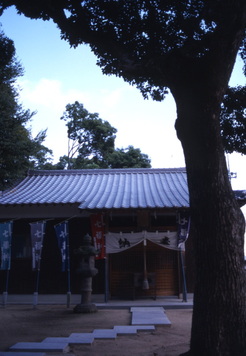

Shirakuni Shrine, Himeji. Shirakuni Shrine, Himeji. Where can you find a really, really big tree in Himeji city? You can’t. The City would like you to believe that a standing, living tree does not create jobs. But cutting one down does. And for the past few years I have borne sad witness to an industry that has turned tree doctoring into ‘tree butchering.’ Before the relentless summer heat arrives, small trucks of hard-hatted men with chainsaws disperse throughout our city shaving and snipping, chopping and chipping, wiping out the very shade and oxygen-giving botanicals that we need! Yet in this sprawling western Japanese city, unplanned and mismatched in every sense of the architectural word, small green spaces exist. They are pockets of calm, oases, where a forest giant or two rises, birds congregate, highschool kids smooch and elderly toss coins, clap their hands and bow into the warm, fragrant depths of Shinto shrines. That’s right, I’m talking about the abode of the Gods: Shinto shrines. My local shrine sits on a tiny knoll cut off from the world by a rice paddy sluiceway and a luxuriant wall of foliage. Out of this rise two enormous kusunoki (camphor trees) and at the foot of them stands an old weathered Shinto shrine, pelted by bird poop and succumbing to creeping moss. It is the quietest place in the Good Hood, a traditional neighborhood north of Himeji Castle and my home away from Australia for the past 14 years. So there I sat this morning, on a poop-pelted bench, watching feathers and fruit stones fall from the canopy and shafts of morning sunshine illuminate patches of fiery red spider lilies. Beetles whirred and butterflies flitted through the undergrowth. The reason such life exists is because the grounds of a Shinto shrine are sacred turf--off limits to the little men in hardhats with the biting saws and stinging blades. Trees are the realm of Shinto gods. They are untouchable. My troubles dissolved, I left through the torii (Shinto gateway) refreshed, my mind emptied and at ease, ready for the surge of new knowledge, stimulation and stress that each day brings living in Japan--a country which, despite its traditions, prides itself on living at light-speed. Next week: The Good Hood celebrates Autumn with colour, noise and plenty of hops.

1 Comment

A coffee syphon bubbles. Ching! goes a toaster. The doorbell jangles and in walks a man with a limp and sweat on his brow. He shoots a glance at the counter staff and says:

“Iced coffee. Make it cold.” Behind a newspaper a customer sniggers. “Big night, Fujimoto-san?” the staff asks, jiggling cubes into a glass. “Is there any other kind?” He jabs a cigarette between his lips and like a cowboy with a gammy leg hobbles into the cafe’s depths for a quiet smoke ahead of his coffee. The syphons are really bubbling now, like a mad professor’s chemistry set, filling the shop with every aroma from Java to Jamaica. Customers enter in ones and twos and the counter talk is of the nation’s big run on earthquakes, typhoons, tornados and floods in the past week. But I (and these customers) digress. This week’s commentary is on the ups-and-ups of good caffeine hit in the Good Hood, a traditional neighborhood in Himeji city, western Japan, and my home away from Australia for 14 years. While the Way of Tea (cha-no-yu) embodies Japanese sophistication, it is coffee which drives the nation. This is no hat-tip to Starbucks, Seattle’s Best et al. No-no, I’m crediting a far more humble and deserving institution; one that sends the suited battalions off to work each morning with hot coffee and hearty breakfasts in their bellies. I’m talking about the KISSATEN (“keesa” for short): the train station cafe, the sidestreet coffee shop, the neighborhood information hub, morale raiser, instiller of “wa” and neighborly camaraderie, a place where you can be alone but not lonely and have your coffee personally brewed. So it is at Cafe Tiffany which sits beside the slow-moving Ono River on the west side of the Good Hood in Himeji city. It is home to the hobbling cowboy, several chain-smoking housewives, one drunk-by-lunchtime retiree, a lively senior citizens’ croquet team and a swag of other colourful, friendly characters who are so regular they don’t even need to order--a morning greeting suffices. To my knowledge, nowhere in the Good Hood does a cup coffee come at the click of a button, nor in a disposable cup. It comes from a bean that is milled. That is percolated in a glass syphon with hot water that is heated over a white spirit burner. And that is served piping hot in a fine china cup ON A SAUCER. And that’s not all; order before 10:30am and you get a fat wedge of almond-butter toast, a salad with shiso dressing and a hardboiled egg. For it all you pay the yen equivalent of a few bucks. Last week I warned you off a place I call the “Ginz.” But elsewhere in the Good Hood there are no other such landmines. There’s the Laugh Laugh Cafe down the street, a not-for-profit business that gives special needs kids a chance to acquire business and social skills. There is Cafe Parland, run by a friendly young couple who have reversed the demise of my old neighborhood by building a large, airy wooden restaurant-cafe where people come even from outside the neighborhood to eat healthy Japanese fusion cuisine and shoot the breeze over a good brew. I like this place a lot. I like the funky toons, the potted jungle, the natural wood bench seating with wide windows that look out onto olive trees and a herb garden and give you a front seat to the wild Autumn weather everyone’s been talking about. And I LOVE the knockout espressos. Drop by, let’s knock ourselves out together! Next week: I have no idea. But after this next espresso I might. |

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed