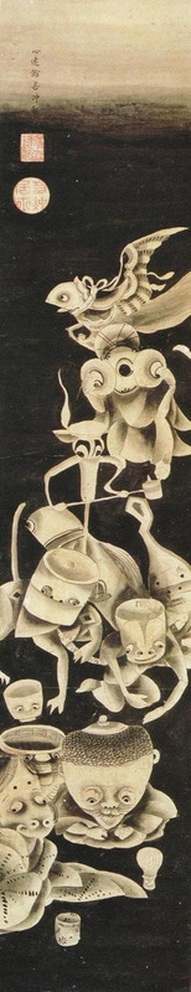

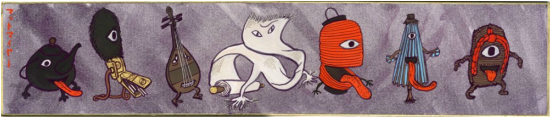

"Tsukumogami no tzu" by Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800) "Tsukumogami no tzu" by Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800) Stands to reason that in tough economic times, people spend less on luxuries and more on small pleasures - like beer, cigarettes and Uniqlo underwear. A new rooftop beer garden opened in Himeji last week (two floors above Uniqlo), affording more skyline drinking space for the hard-working denizens of this town; another place for them to catch a cooling Inland Sea breeze, run their snouts through the all-you-can-eat buffet troughs and drink whatever it takes to forget those tough economic times ahead. When will they end? They may never end. The bean counters in Tokyo would like them to end because people who don’t spend keep prices down, which keeps salaries down, which forces retailers to cancel each other out in fight-to-the-death discounting wars. But you can read all about that in the papers. There is another, less sophisticated way to measure consumer spending in this country. It goes like this: twice a month, usually at dawn, in villages and towns and cities across the archipelago, Japanese shuffle to a designated spot - a street corner or carpark - and toss out their unwanted household goods. This purging of solid waste, called sodai-gomi or “BIG rubbish,” is both a barometer of economic ‘health' and a measure of excess. Let me explain: Back in the Bubble period of the 1980s, materialism went berserk; big companies issued juicy bonuses twice (sometimes thrice) yearly to their workers and a newly-arrived foreigner with zip to his name could furnish his home with two or three trips to sodai-gomi collection point. The pickings were fat: Onkyo stereo systems, Panasonic vacuum cleaners, Toshiba refrigerators, heated tables, snowboards, scuba diving gear, pachinko machines, suitcases filled with dildos (sighted) - many of them abandoned for no fault of their own other than they had ‘lost their sheen.' The ghosts of those ‘gaijin gomi hunters' still haunt the late night and early morning junk piles, or what little there is of them. See, now that company bonuses are down, only really boro-boro household appliances are released from servitude. Which leaves the professional scrap metal collectors to fight over the greasy microwaves, bent futon poles, cracked coffee makers and wheezing electric fans. It's a solemn species of man who does this job. I pulled my sodai-gomi duty last week. By some weird design, I was paired with Smokin’ Joe Matsumoto, my friend the old kitchen gardener who lives down the street. For three times a year we get to play Big Kahunas of the junk heap, greeting our neighbors, helping them with their empty beer cans, bottles and newspapers, reaping news of who has died, gotten married, gotten divorced or gotten a hip replacement, and generally facilitating this ‘bush telegraph' until 8am arrives and we split for coffee and cigarettes. Some observations: low-malt (cheap) beer consumption is up, so is cheap Chilean red wine, sake is down, newspaper readers are down, too. In fact, year on year, the size of our trash heaps grows smaller. Blame it on a languishing economy? Or maybe a disappearing neighborhood? “Old people think old. If it's not broken, they don't throw it away. If it is, they mend it," says Smokin Joe. He lights up, puffing thoughtfully. “A lot of elderly still believe in “Tsukumogami," the ‘Gods of Useless Things.' They believe that when a tool or a container or a piece of kitchenware reaches the 100th year of its working life, it receives a soul. And that must be respected.” Tsukumogami belong to the yokai world of Japanese ghosts, goblins and other mythical trouble-makers, and while they're generally harmless, they can be mischievous, says Smokin. “They can take revenge on owners who are wasteful or thoughtless." Days later, in the cool depths of the Himeji Museum Library, I found an example of the Tsukumogami yokai: the Boroboroton, or possessed futon. It warned against leaving your futon out in the rain, eating food or spilling drink on it, forgetting to air it and clean it, for one dark stormy night it will rise up, toss you out, entwine itself about your head and neck and strangle your worthless, lazy bones! The caption beneath this horrifically graphic depiction in the book read, “A Boroboroton will come to life when feeling ignored or needless." Fair enough. Other potential mutineers in your household are the Kameosa (possessed sake jar), the Zorigami (possessed clock) or the Ichiren-bozu (animated prayer beads). And may the Gods of Useless Things have mercy on your soul should you do wrong by your Yamaoroshi; couldn't think of anything messier than a fight with a possessed radish grater. Ouch.

2 Comments

A long time ago (250 years thereabouts), a powerful dude named Sakakibara Masamune decreed that the people of his castle town slip into something more comfortable and shimmy downtown for a good time. “Do what?” his attendants asked. “Throw a party, you monkeys. I’m outta here!”

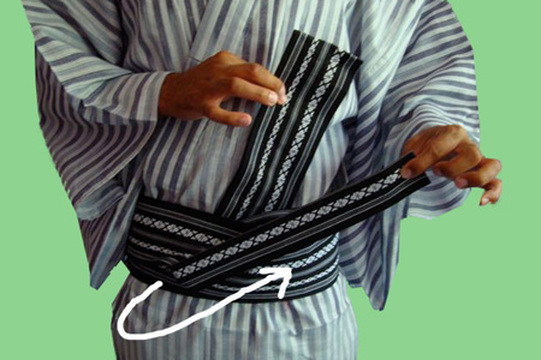

Indeed he was, off to rule another fiefdom, but not before starting a tradition that would fill the fine streets of Himeji with colourful summer kimono (ゆかた, yukata), octopus dumplings and (centuries later) skyrockets and riot police, for three days a year, every year thereafter. More than just a celebration of the highly functional yukata, it’s a fashion show. Women’s yukata colours are brighter, patterns livelier, and horror!--hems are rising. The elderly women of the Good Hood shake their heads and click their tongues at these parading young things in micro yukata; the young fellas nod their heads and knock themselves out with their tongues. The Yukata Festival, held June 22-24, also celebrates the rainy season. That’s right, it is the WETTEST time of the year (and news just in: rain is forecast for Tuesday, June 23nd) which doesn’t stop several hundred thousand people from choking the streets and alleys south of Himeji castle with coin to spend on cold beer, toys and tasty treats. Catering to the masses are more than 800 stalls, erected and manned by a small army of itinerant carnivaleers called tekiya. Word on the street is that tekiya are in cohorts with the local yakuza; others say that’s an unfair image and that the stall holders are just abiding by a ‘system’ which takes a nice slice of their earnings and hands it to the mob. Let’s call it a ‘licensing fee’. The City seems OK with this as it ‘stimulates’ the local economy and frees up their rubber stamps for more pressing matters. Times have changed since I tagged along with some English teachers to my first Yukata Festival 15 years ago. Then, youth gangs flocked from all over the province to wage theatrical (and sometimes violent) running pitched battles with their rivals on the city streets. Hard to believe in peace-loving Japan? Well listen to this: watching riot police get pelted with skyrockets, drag troublemakers off to paddy wagons by their orange hair, and see the odd motor scooter get barbecued, reminded me of the Costa Rican fruit vendor riots of ‘91 (Yes, I was in Costa Rica in 1991). Cheap entertainment for the masses, poor public relations for the police, not exactly a festive family affair. That’s all gone. The police have changed their tune. They now use subterfuge and infiltration tactics, clever stuff like putting dozens of plain clothes officers into the crowds to catch troublemakers on digital camera or video. Maybe this has worked, or maybe the young punks have just gotten older, gotten married and gotten a job, because the Yukata Matsuri IS now a family affair. ‘Smokin Joe’ Matsumoto, the old kitchen gardener who lives on my street in the Good Hood, will be taking his grandchildren again this year. Those long sleeves of his faded yukata will be sure to hold a pack of cigarettes, a lighter and some coins for cotton candy. My old friend Ono-san won’t be going; she thinks it’s too crowded, too noisy, the food tasteless and too expensive. “I’m saving my yukata for the fireworks festivals,” she says. If YOU go, be sure to drop by the Ghost House at the edge of Otemae park; it has been a going concern for years, adept at taking your money and scaring the beejeezuss out of you with the screams of other teenage patrons. They say a good ghosting chills you out during a long, hot Japanese summer. Personally I’d prefer a cold beer...  Tameshigiri - live target cutting Tameshigiri - live target cutting Souke, my sword teacher, gave a speech at our annual gala performance last weekend. She reiterated what all teachers have said at least once in their lives: that making mistakes is vital to the learning process and that fear of failure can lead to unnecessary anguish. To press her point she told of how, as an elementary student over a half-century ago, she performed an entire dance routine with a tack in her foot because she couldn’t remove it by herself and didn’t want to bother her teammates with the trouble. Ouch. Now in her 60s, she is worldlier, wiser, has sold her Hummer II and given up Camel Lights for low-tar alternatives. She is as nimble, quick-witted and supple-limbed as a teenager, presiding over the nightly sessions of iaido (the art of sword drawing), senbu (fan dance), kenbu (sword dance) and shigin (詩吟, poetic song) at her dojo of Kanshō-ryu (the Flying Crown sword style) in Himeji city, western Japan. I remember how, only six months after walking through her door, she placed a shinken (‘live’ sword) in my hands; a blade that could have spliced the nose hairs on a fruit fly. It felt like an electric eel between my sweating palms—light, hot and flighty—and I handled it nervously, worrying that each time the blade departed the sheath, I was putting myself and the whole world in peril. I didn’t show my fear during practice, but the day I walked onto the stage at the City Culture Centre, three weeks later, I could hardly contain it.  The Flying Crown sword style in action The Flying Crown sword style in action The Dai Hall was packed. There was standing room only for the big name kabuki star who was to appear later (our dojo providing the supporting act). While Mister Kabuki was calmly powdering his face out back, our dojo members sat in nervous ranks along the stage, concealed behind a long, heavy curtain. From the other side of this came the hum and murmur of 1,600 people—a cough here, a whisper there—belying the ocean of expectation which lapped at the stage. The older, experienced dojo members around me focused themselves, breathing deeply. The newer members fought to keep their Adam’s apples from defying gravity. “Standby!” came the stage hand's call from the wings. The curtain rose, and our dopamine levels with it. The stage filled with whirling black hakama and the flashing sword blades of iaidoka performing kata to the best of their ability: hangetsu (the half-moon cut), fūjin (the wind god cut), fubuki (the blizzard cut) and on they went until it came time for the tameshigiri, the stylised cutting of rolled tatami mat poles. One by one, the targets fell in clean sweeps. In the Japan's Edo period (1600-1868), tameshigiri was performed on dead (and sometimes live) criminals to test sword blade-strength. Then it was my turn to perform michizure (みちづれ). Roughly translated it means “the highway companion.” It's a technique which I feel embodies the philosophy of iaido and its so-called “moving Zen" form, in which the swordsman, perceiving the threat, acts on it clearly and cleanly. In the case of michizure, the 'threat' is an assassin tailing you. Thrust. Pivot. Strike. I remember the blade easing through the tatami fibres, the foul-smelling and water-logged roll drop with a thud to the stage floor. As I returned the blade to its sheath, something bit my hand. A wet warmth glided down my fingers. I glimpsed blood on my toes but resumed my seiza position, pressed my hand into my hakama to stem the flow, and bowed. The audience applauded, none the wiser.  Slice and dice... Slice and dice... The most shameful mistake a samurai could make was to cut himself. Relieved, but despondent, I shuffled offstage. A veteran swordsman caught me by the sleeve and pulled me aside. “Nerves only get in the way," he gravelled. “Empty your mind and get on with it.” Seven years on, and countless performances since, those words still resonate. Failure never enters my mind when the sword closes on its target now. The blade does the hard work. The handler only sets it in motion, giving speed, angle and timing. I still attend our dojo’s twice weekly training sessions, marking my progress by scarring, gashing, pock-marking and carving the floorboards and ceiling beams. I even managed to tear my hakama with my sword tip recently. But I see veterans do the same; they drop their fans, stumble and snag their spear tips on floorboards, forget their moves and stand dumbly as the music continues without them. While she might bark and growl at these faux pas, Souke forgives. She still makes them herself. As the saying goes, 猿も木から落ちる. “Even monkeys fall from trees.” *Moving Zen Part I appears in the May 2014 archives.

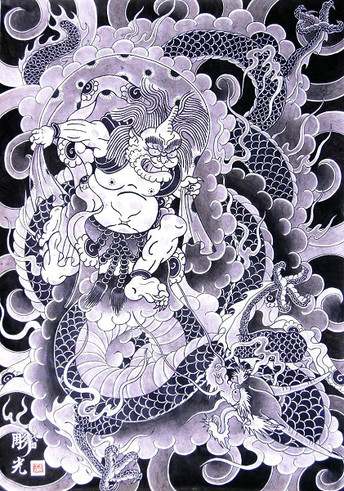

Jorogumo spider. Image by John Harvey Jorogumo spider. Image by John Harvey I have a revolving door policy for insects great and small in my house; the logic being that big insects (spiders) eat small pesky ones (roaches, earwigs, mosquitoes, fruit flies and clothes moths). Which is generally a good thing—until the wet season arrives in western Japan. The first meaningful rain of June fell last night: a long, slow drizzle that filled the flower pots and beat down on the roof tiles of the empty houses in my neighborhood. It is a precursor to the equally long and torrid wet season, now looming off the coast of southern Japan. Not only does rain bring restlessness to my old house (timbers expand, paper doors ripple, tatami mats sag) but to the insects who venture from its nooks and crannies in search of food and romance. Or, where my living room is concerned, liquor and late night TV. So the long rain fell on into the night and there was nothing for it but to ease out the tide on a bottle of Black Mist Island shōchū (焼酎) and watch Zatoichi, a film about a blind ronin who wanders the highways of old Japan slaying anyone annoying or who smells bad. I jiggled my ice cubes, listened to the thunder and waited for Zatoichi’s next head to roll. In the darkened corner of the room something moved. From beneath the tokonoma (a sacred hearth kept by most traditional Japanese houses), a monster yorugumo, or night spider, emerged. This was no washed-out Incy-wincy—it crossed the tatami mats like a small cavalry unit with the leg-span of a kid’s tricycle wheel. Zatoichi hid in the shadows. The next evening the spider was back, drumming his feet on my paper sliding door, looking unimpressed, and in the words of Raymond Chandler, “as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food cake.” A tarantula? This huge, hairy bastard would have eaten ‘em with cornflakes! Now I don’t like to kill anything, but since the cockroaches had disappeared, I wondered what next lay up the food chain? Then I remembered an old Japanese superstition: “if you spy a spider in the morning (asagumo), you shouldn’t kill it. But if it is a night spider (yorugumo), then it means bad luck and you should SMASH it!” I pulled from the closet my Toshiba GH-0971 and plugged it in. The room vibrated with the sweet sound of doom. The spider broke into a gallop—the cavalry headed for Death Valley. The great thing about the Toshiba GH-0971 is that it has extensions! A large insect going up one sounds a lot like a fat man being blasted from a cannon (only in reverse). That strange plopping noise caused me to reflect. I said three なむだぶなむだぶ, invoking the name of Buddha, and returned the GH-0971 to its mantel. Guess I should blame the warm, humid southerlies rising from the Philippines for this mega-fauna. Rain sets off a growth spurt which culminates in an abundance of bug life; spider webs festoon the telephone lines, abandoned houses, disused bicycles and futon-drying poles of my neighborhood. Japanese folklore endows these creatures with supernatural abilities—to transform into boys or women, like the large-bodied Tsuchigumo, or Earth spider, which tries to lure the samurai commander Minamoto no Yorimitsu (top picture) to his death, but is itself fatally vanquished in one famous tale. Or the Jorōgumo (the “femme fatale" spider), which is said to assume the body of a beautiful woman and to have once seduced passing samurai, whereupon she wrapped them in silk and sucked them alive. Actually a member of the golden orb spider family, the jorōgumo is venerated as a goddess at the Jōren Falls on the Izu Peninsula, where she is said to save people from drowning. From mythical doom to modern day gloom, the new scourge, according to the Japanese media, is the Australian redback spider ‘plague.’ Did you hear correctly? Yes, you did. The story goes that, 20 years ago a container ship carrying Australian wood chips docked at Osaka port and, once the captain and his Filipino crew had taken leave, the redbacks (Latrodectus hasseltii) slipped on their Hawaiian shirts, sunglasses, and with extra supplies alpha-latroxin taped to their chests, sneaked by Osaka Customs and Quarantine to kiss the earth of their new homeland.  Unwanted and unloved - Latrodectus hasseltii, aka redback spider. Unwanted and unloved - Latrodectus hasseltii, aka redback spider. I loathe journalistic shortcuts like “Experts estimate…” but let me use it just this once: “Experts estimate there are now more than 19,000 redbacks in Japan. As of Oct 20, 2014, 100 people had been bitten with no fatalities.” According to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation report, a nice man named Dr Koichi Goka from the National Institute for Environmental Studies, believes the Japanese medical system is not prepared for the spread of this spider: “The medical system is behind. They have anti-venom in Osaka and Fukuoka but other provinces don't have supplies. So it's a serious issue and hasn't been addressed," he said. The report also says that the spiders have no natural enemies here and that heating systems (toilet seats noted) have helped the spiders to survive Japan’s cold winters. And finally, this gem: “Japan experts warn it is possible that redbacks could mutate and return to Australia with a stronger, more toxic bit.” Are you kidding me? Why would anyone in their right mind want to leave a country with heated public toilet seats?  Classic Kirin Lager poster. Classic Kirin Lager poster. “The problem with the world is that everyone is a few drinks behind.” ~ Humphrey Bogart The problem with Friday nights in the Good Hood is that everyone is a few drinks ahead. Which is not to say that I’m a slow drinker—I’ll raise my glass to your health as fast as the next drunk—it’s just that by the time I've finished work, helped with the chores and read Harry the Dirty Dog or Where The Wild Bums Are to the little people of my household, Hana-kin is almost gone. Hana-kin means ‘Flower Friday.’ Seasoned drinkers who survived the dancefloors and big hair of Japan’s 80s Bubble era still use the term to describe the day when a week’s worth of paper shuffling, screen-staring, drifting through meetings and endless trips to the green tea dispenser comes to an end, and night and city beckon. To Japanese youth, the term Hana-kin is archaic—like grandad’s shoestring neckties or Tahitian Lime hair tonic—and likely conjures images of drunken businessmen singing karaoke with neck-tie bandannas while their junior female colleagues pour drinks and mop up the vomit of those who have passed out. It is true—I have borne witness. And yes, the youngbloods are right, Hana-kin does need an image upgrade. The gap between old and young doesn’t bother me; I feel equally at ease in the raucous dive bars on Himeji's Salt Street and the faux wine bars of Fish Town Street. But in the end, there’s no place like home, and my home for the past 18 years has been the Good Hood north of Himeji Castle, an old neighborhood which survived the WWII firebombings and still breeds a sense of true Japanese community. I like to drink with ‘my people.’ That’s why on Friday nights, whenever I can, I make for a place where the salt-of-the-earth gathers like a crust on the counter. To the Poodle Bar! The Poodle sits at the confluence of a busy street and the deathly quiet one which leads into my neighborhood. Before the roller door goes up around 6pm, the counter has been wiped, ashtrays set at half-metre intervals, toilet scrubbed and the karaoke volume adjusted downwards from the previous night. Around 7pm, the first customers drift in, the early birds, the oldtimers, pensioners, widowers, maybe a retired mobster or two. Later, their seats will be taken by factory workers, truck drivers, lonely single men and the odd housewife on-the-run. Come on in, take a seat and start your night with the words, “Tori-aizu, biru!” or “A coldie for starters!” There’s nothing like a glass of brown bubbles to slacken the jaw and loosen tongue. But tonight, as on most Fridays, the seasoned drinkers are ahead. For the pensioner, the two grease monkeys with calloused knuckles, the huddle of smoking housewives and the jokester singing “Top of the World”, that first beer is a distant memory. Bottles of Black Mist Island Shōchū (焼酎) now line the counter, the ‘bottle keeps’ of these regular patrons, each bearing the name of the man or woman in front of it. This is serious drinking, Mum, the kind that makes an Irish funeral wake look like a child’s tea party. Tonight promises to be a king tide at the Poodle Bar. Tonight all boats will be lifted, some may lose their rudders, others will flounder and sink, and the lucky ones will limp home to port and a dry dock for the rest of the weekend. The unlucky with be bundled into a taxi and driven to an address of their best pronunciation. The Poodle Mama oversees this night-time circus with the ease of a woman who sees it every Friday night. She is a woman in her late 50s who looks like what Raymond Chandler might have called a “drawn-out dame.” Her makeup is thick, I cannot tell if she is smiling or grimacing as she moves between patrons, pouring beers, working swizzle sticks, encouraging the money flow across the counter. Will she sing a song? Will she? The pensioner pleads. His cajoling ends in a sad (very sad) ballad about love lost in snowy Hokkaido. The Poodle Mama is clapped off vigorously by the young mechanics at the end of the bar and a greasy microphone is thrust into my hand—with a song pre-selected. And so once again, the deathly quiet street which leads to my home resounds with the words, “On a dark desert highway, cool wind in my hair, warm smell of colitas rising up through the air…” Admittedly, closing time at Poodle is an hour I seldom see; the messiness, mayhem and mumbling missing persons reach me only as sounds lost in the night, when I am safely tucked up in my futon and dreaming of water skiing bikini girls and a warm tide lapping at my toes. Which reminds me... If I ever open a bar here, I will call it the High Tide Bar and I will raise a neon sign over the counter which will read in atomic orange kanji, “If you drink to forget, please pay in advance.”  "Travellers surprised by sudden rain" - Hiroshige woodblock print "Travellers surprised by sudden rain" - Hiroshige woodblock print It wasn’t a warm wind that crawled through the Good Hood of Himeji city last night. It was an Arctic blast with a knife edge and it wailed like a crazed woman through the cracks of my old mud-walled and tiled-roof house. Hundred-year-old dust drifted from my ceiling while the paper doors rattled like old bones in their grooves. Outside the din was worse: empty beer cans somersaulted down the street, telephone lines whined and a drunk fell off his bicycle somewhere near the Funabiki Barber Shop around 2am, got back on it a half-hour later. The Siberian northerlies I blame for my sleepless night ― the last chill breaths of the Wind God, Fujin, before spring well and truly sets in. That process has already begun; the warm air pushing in from the Philippines is beating winter back across the Japan Sea. It’s a tussle that always ends in tears over Honshu. As predictable as the Japanese themselves, the weather last week was thus: rain, rain and more rain. It was bad news for Hanami party-goers who huddled beneath the cherry trees of the newly-restored Himeji Castle drinking good sake cheapened with rainwater. Trees shed their blossoms in pink blizzards and rivers and moats ran the colour of strawberry milk, a wash-out worthy of tears for those who had turned out with bento and booze to celebrate the beginning of all new things. “The life of a cherry blossom is like the life of a samurai,” says Smokin’ Joe Matsumoto, the old kitchen gardener who tends a field beside the Semba River at the end of my street. “How so?” I ask, hoisting my umbrella against the soft drizzle so he can light another cigarette. “Short and beautiful,” he says. “Like your neighbor Ms. Hayashi.” He fixes me with his bloodshot gaze, searching my own. “Don’t get any funny ideas. She’s got a boyfriend. He's yakuza.” There’s a point, where if you stand just to the left of Smokin’s onion rows, you can glimpse the sweeping roofs of Himeji Castle’s main tower as they rise above the rooftops of the old city neighborhoods. I thought of the lovely Ms. Hayashi, her mobster man, the castle veiled in drizzle and the mud on my boots and murmured, “Pure misery.” “What?" “This rain," I said. “Harusame. Spring rain never lasts.” True ― one kind of rain is merely replaced by another in Japan. The steady drizzle and lingering mists of harusame are preceded by natane-zuyu, or ‘rapeseed rain’, with its sudden downpours and droplets that can fill a sake cup within minutes. Gardens of the Good Hood surge on this abundant rainfall; bulbuls wing down from the mountains to feast on the new growth and the inhabitants thank the heavens for temporary respite from the hay fever-bearing cedar tree plantations in the north. There will be further rain, on and off until the mighty tsuyu, the wet season, arrives in mid May. Then, the aging residents of my old neighborhood will know that spring has truly passed and that the Good Hood has once again completed another 940 million-kilometre circuit of the sun. I bet all this travel makes them tired. Smokin’ Joe takes the umbrella from my hand, folds it and hands it back to me with a bunch of red onions. “A famous samurai movie actor once said to his sidekick, “春雨じゃ, 濡れて行こう!” “Meaning?” “Spring rain's here. Let’s get wet.” I laugh, he laughs. Rain is the one true constant at this time of year. So we set out along the river path for home ― the old samurai and his sidekick ― with a swagger that sets our onions swinging.  “And so castles made of sand, fall in the sea, eventually” ― Jimi Hendrix A house razed, a rice paddy paved, year after year the air flows more easily through the streets of the Good Hood. My elderly neighbours pass on, leaving their grand old homes to crumble and fall, or to be sold off by distant relatives and crushed by the demolition men in peppermint green uniforms and pink excavators. The other day I paid a visit to the real estate agent to ask about a vacant lot where dear old Mrs Mizutani and her home once stood. Asking price for the overgrown lot? The agent punched his calculator and pushed it across the table top. Holy Buddha, man! I could build a small Taj Mahal for that, I said. He shrugged, pocketed his Casio and glanced at the smoker’s room. The Good Hood, a traditional mud-walled and tiled-roof neighborhood in the seaside city of Himeji, has been my home for 17 years. Its narrow streets have outlived WWII fire bombings, earthquakes and typhoons; it has sheltered bank workers and barbers, steelworkers and old mobsters with faded tattoos, foreign English teachers and their countless girlfriends, and now snakes, bats and exotic pets-on-the-run inhabit the deserted homes... But like all the aforementioned, the Good Hood is succumbing to that one true constant ― old age. “Nothing lasts forever, not even a rock,” says my old friend and kitchener gardener, Smokin’ Joe Matsumoto. He lifts a stone from his onion patch and heaves it into the Semba River, the waterway which cuts a meandering path through the Good Hood. He lights a cigarette and recalls the American B29 Superfortresses passing over Himeji on their way to unload on the fighter plane factories in Kobe in 1945. “They flew low, in big formations with sunlight glinting off their wings. So loud.” Ono-san, another old friend, will never forget the sticks of firebombs falling on south Himeji as she evacuated with thousands of others for safety of the mountains. “Like a fireworks show ― beautiful, deadly.” The other true constant in this city (beside bad drivers) is Shirasagi-jo ― the White Egret Castle. You could say it is Himeji’s reason for being. It is my reason for being, because as the old houses around me are demolished, my view improves! Where else could I wake to the sight of dawn creeping over a 500-year-old samurai castle, then stick my head through a window and sniff Tahitian Lime hair tonic from the barber shop down the street. The hardworking people of this town will next week head en masse to the Castle grounds, to roll out their picnic sheets and tilt their glasses to the cherry blossoms, drink to new classes, new jobs and new resolutions (for those who gave up ‘giving up’ in February). Unlike the Good Hood’s old houses, the Castle is deemed too precious to let self destruct ― a no-go zone for the peppermint men and their pink machines. So six years ago, the city passed the hat and raised ¥2.4 billion from donations, taxes and national funds to give the old dame a facelift. For five and half years a shroud kept her face hidden; only a constant tapping, clanging and banging belied the work of a small and dedicated army of crafts folk who, using traditional materials and means, patched, plugged and painted her back to her prime. Last week, beneath the vapor trails of those magnificent men in their flying machines - the Blue Impulse aerobatic team - Shirasagi-jo finally opened. Nothing lasts forever ― true. The green and pink demolition squads will keep visiting the Good Hood, dropping old houses to make way for smaller, cleaner, brighter ones, and the land agent will get his commissions, the English teacher his new girlfriends, the snakes their frogs, and so on and so on down the food chain until my own mud, bamboo and tiled ‘castle’ will succumb to that one true constant and fall in the sea, eventually. Next week: The one true constant ―Part II: ghosts, swordsmen and movie stars of Himeji Castle  The Good Hood's portable shrine takes to the streets. The Good Hood's portable shrine takes to the streets. Rolling thunder? Hunger pains? Another murmur from the Yamasaki fault line? No, that deep rumbling sound which fills the night sky over the Good Hood is the sound of a festival brewing. The beat of the taiko drum heralds the approach of another year’s worth of shoulder pain, chanting, sweating, drinking and more drinking, all crammed into one day in October. There’s not a moment in the Himeji city when I feel closer to the soul of Japan than atmatsuri (festival) time. When the smell of burning rice chaff signals the end of the rice harvest and the sickly sweet aroma of the kinmokusei flower fills every street, lane and alley. Matsuri! Matsuri! The sound of drums can be sourced to the backyard of my Jichikai-cho, the neighborhood Boss, and our elaborately decorated centrepiece, the omikoshi, or portable Shinto shrine. Generating the thunder are the small arms of the neighborhood school kids. Two weeks before festival day, they hammer volleys into the night sky, honing their skills, perfecting their rhythm for the big day. One day before the festival, the Boss summons me. An extra pair of hands is needed to assemble the omikoshi; it’s an intricate and fiddly job which entails bolting, knot-tying, binding the shrine and attaching ornaments to its housing. When preparations are complete, six packs are passed. Quiet slurping and furtive glances towards the sky follow.Will Raijin the God of Thunder stay away tomorrow? Across the archipelago, autumn festivals are thrown to honour the Shinto gods and give thanks for the rice harvest. But as my good friend Ono-san laments, it’s a meaning too often drowned in drinking, eating, macho posturing and the excitement of carrying the omikoshi. I reply: “And you think Christmas is just the Big Man’s birthday?” The night before the festival, our illuminated omikoshi ventures into the streets swarming with school kids and pushed and pulled by fathers who have escaped the office early. Lanterns hang from residents’ porches like overweight glow worms. The omikoshi moves slowly, like a dinner cruise boat along darkened laneways. Festival day breaks with a clear crisp dawn. I don my blue festival jacket with its giant red kanji character for “festival” on the back, shake the night’s hangover from my head and secure by self-pity with a red bandanna. The Boss gives a speech. Cups of sake are passed. Died squid jerky, too. A staccato drum beat sends the men to the yokes and together we carry the omikoshi to the local shrine to be blessed by the Shinto priest. Joining us are other neighborhoods, their omikoshi topped with dancing lions and decorated with tigers and bamboo, each supported by an entourage of mothers, wives, kids, babies in prams and the occasional lost tourist. The day wears on, the sun beats down, bento and beer flow, and through the Good Hood the omikoshi rumbles and rattles like an old war horse. The sound of its drum brings residents to their doors bearing envelopes of gift money. For this they receive a boisterous, semi-drunken chant and vigorous shaking of the shrine by its bearers.

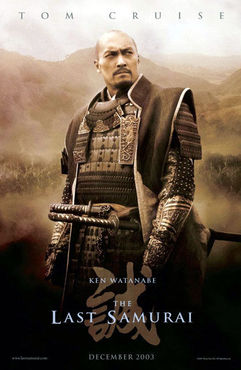

Rice millers, tatami weavers, barbers, tea shop and restaurant staff come out of their shops to cheer us on. To a destination I’m no longer sure of, or even care. The omikoshi becomes a lifeboat for those who have drunk too much. Stay with us! Don’t let go! The taiko beat feels like a huge rolling rock inside of our heads. By late afternoon the chanting eases, the fall of the drumstick dependent more on gravity than energy, the bearers are tired, the drummers slightly deaf and the mothers’ auxiliary strung out in the streets behind us; only the babies waking from their afternoon sleep are punching the air. On sunset, as the crows fly north overhead, we give thanks for another great day, then set to work dismantling and packing away the omikoshi for another year. Once the roller door is pulled shut, I turn and head for home, bone weary and beat. The Boss summons me. I cringe and turn slowly to face my fate: the other annual tradition in the Good Hood I forgot to tell you about -- the matsuri AFTER PARTY!  Summer has left my old friend Smokin’ Joe Matsumoto a broken man. Not quite broken, more like washed up; the heavy rain and typhoons which rolled through the Good Hood of Himeji this year ravaged his kitchen garden and left him king of a teeny weeny harvest. Even the watermelon thieves passed his patch over this year. I have never seen a man smoke a cigarette more despondently. He tosses me an eggplant the size of light bulb, wearing a frown that could hold rainwater. “Don’t take it so bad. The watermelon thieves will be back next year,” I say. “Hardy-hah (Japanese equivalent),” says he. “How’s your slug problem?” “I’ve run out of salt.” “You should move out of that old house.” “That’s what I tell the slugs.” “What do they say?” “When Buddha wills it.” “You should talk to Buddha.” “I’ll Skype him tonight.” “I mean you should REALLY talk to Buddha. Climb the holy mountain and talk to him.” “What holy mountain?” “Shosha-zan.” “You mean the place where they filmed The Last Samurai?” “Never seen it. What's it about?" “It's about a small American guy with a big nose who forces the samurai to speak English." “We leave at dawn." And so, with emotional baggage to purge, the Australian and the old Kitchen Gardener wobble off into a September dawn on bicycles they can only dream of burning their names in the road with. Shosha-zan, the ‘Mount Hiei of the West,’ is a holy mountain, home to a small Buddhist community of the Tendai sect, on which the towering Engyoji temple pavilions serve as its centrepiece. At this hour the venerable mount lies wreathed in mist, a sleeping giant on the outskirts of the city. We ditch the bikes and through rice fields clouded in dragonflies we hike, before ascending a zig-zag path through rock, scrub and cedar forest, until the air cools and the sounds of the city fade into bird song. I keep two strides ahead of Smokin’, who, at 71 years old, believes progress up a mountainside is measured not in mossy stone markers but in cigarettes smoked. Kudos to him when he holsters his Zippo at the edge of the old wooden temple precinct. There, a monk in black and white robes stands waiting in the courtyard. He is a big man with small round spectacles which balance on his nose. He, too, is dwarfed by the thousand-year-old pavilions with sloping tiled roofs and gargoyle keepers. The monk holds a long wooden paddle in his hands. He pats it gently against the palm of his meaty hand and smiles at our approach. Smokin greets him like an old friend. They are old friends, from an aikido class years ago. With greetings exchanged we are ushered up the steps of Jogyodo, the Training Hall, whereupon the monk halts and turns to me. “It is dark inside and for the next 30 minutes you and Matsumoto-san will be alone with yourselves in the presence of Buddha. Empty your mind, breathe deeply and lower your eyelids. But do not sleep.” He pats the paddle. Into the fragrant depths I step, moving barefoot across smooth wooden floor until I reach the edge of illumination. Rising above us at the centre of the room sits the All-Seeing One, gilded in gold foil and lit from above. His narrowed eyes peer down on us with an infinity of calm. We lower ourselves onto cushions the size of a frisbee, sit cross-legged, forming the circular sign of emptiness with our fingers. We shutter our eyelids to slits, draw deeply on the air and purge our minds of all thoughts of slugs, cigarettes, undersized melons, bikini girls and coconut oil. Time passes. And yet it does not pass. Time is merely a concept, so how can it be measured if I cannot consciously detect any change in my personal circumstance? The answer to that lies in the monk’s big wooden paddle. WHACK! WHACK! WHACK! I must have dozed. For this misdemeanor I take my punishment of three stiff blows to each shoulder and thank my punisher with hands clasped and a reverent bow. Each breath returns me to emptiness and time, once again, begins to fade. Buddha smiles on the two small men from the lowlands. My eyelid pops up. That's it! Watanabe Ken (below) sat beneath this very Buddha in the Last Samurai…. WHACK! WHACK! WHACK! A long time ago (250 years thereabouts), a powerful dude named Sakakibara Masamune decreed that the people of his castle town slip into something more comfortable and shimmy downtown for a good time. “Do what?” his attendants asked. “Throw a party, you monkeys! I’m outta here!” Indeed he was, off to rule another fiefdom, but not before starting a tradition that would fill the fine streets of Himeji with colourful summer kimono (ゆかた, yukata), octopus dumplings and (a little later) skyrockets and riot police for three days a year, every year thereafter. More than just a celebration of the highly functional yukata, it’s a fashion show! Women’s yukata colours are brighter, patterns livelier, and shock! horror! their hems are rising. The elderly women of the Good Hood shake their heads and click their tongues at these parading young things in short yukata; the young fellas nod their heads and knock themselves out with their tongues. The Yukata Festival, held June 22-24 every year, also celebrates the rainy season. That’s right, it is the WETTEST time of the year (and news just in: rain is forecast for Sunday June 22nd) which doesn’t stop several hundred thousand people from choking the streets and alleys south of Himeji castle with coin to spend on cold beer, toys and tasty treats. Catering to the masses are more than 800 stalls, erected and manned by a small army of itinerant carnivaleers called tekiya. Word on the street is that tekiya are in cohorts with the local yakuza; others say that’s an unfair image and that the stall holders are just abiding by a ‘system’ which takes a nice slice of their earnings and hands it to the mob. Let’s call it a ‘licensing fee’. The City seems OK with this as it ‘stimulates’ the local economy and frees up their rubber stamps for more pressing matters.  Times have changed since I tagged along with some English teachers to my first Yukata Festival 15 years ago. Then, youth gangs flocked from all over the province to wage theatrical (and sometimes violent) running pitched battles with their rivals on the city streets. Hard to believe in peace-loving Japan? Well listen to this: watching riot police get pelted with skyrockets, drag troublemakers off to paddy wagons by their orange hair, and see the odd motor scooter get barbecued, reminded me of the Costa Rican fruit vendor riots of ‘91 (Yes, I was in Costa Rica in 1991). Cheap entertainment for the masses, poor public relations for the police, not exactly a festive family affair. That’s all gone. The police have changed their tune. They now use subterfuge and infiltration tactics, clever stuff like putting dozens of plain clothes officers into the crowds to catch troublemakers on digital camera or video. Maybe this has worked, or maybe the young punks have just gotten older, gotten married and gotten a job, because the Yukata Matsuri IS now a family affair. ‘Smokin Joe’ Matsumoto, the old kitchen gardener who lives on my street in the Good Hood, will be taking his grandchildren again this year. Those long sleeves of his faded yukata will be sure to hold a pack of cigarettes, a lighter and some coins for cotton candy. My old friend Ono-san won’t be going; she thinks it’s too crowded, too noisy, the food tasteless and too expensive. “I’m saving my yukata for the fireworks festivals,” she says. If YOU go, be sure to drop by the Ghost House at the edge of Otemae park; it has been a going concern for years, adept at taking your money and scaring the beejeezuss out of you with the screams of other teenage patrons. They say a good ghosting chills you out during a long, hot Japanese summer. Personally I’d prefer a cold beer... |

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed