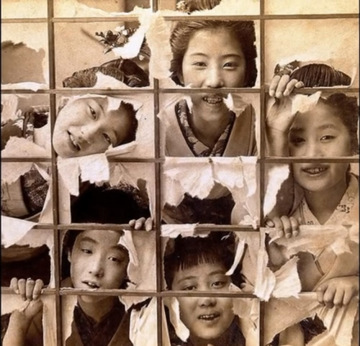

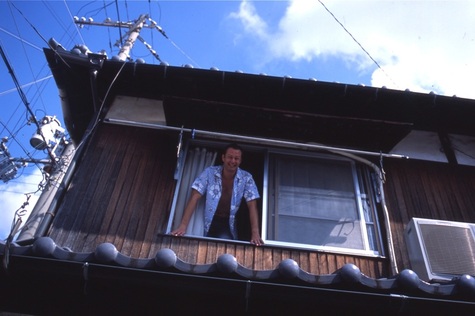

What my papers doors look like now. What my papers doors look like now. “Nothing lasts forever. Not even a rock,” says Kawabata-san, pouring two glasses of beer. He slides one across the table. “To your long life.” Kawabata-san runs the liquor store on the old shopping street near my house. It stands next to the butcher, opposite the yakitori grill, across from the tea ceremony teacher’s house. It has a vending machine outside and the rumble-and-THUNK of bottled beer falling into its hopper is a familiar note in a symphony that fills this street at the end of the day. Coins tumble, bottles rumble, liquor loosens tongues, lubricates conversation, firms up trust and builds friendships - it’s the glue in the social fabric of communities all over Japan and in the Good Hood of Himeji city, too. And so passes an afternoon of drinking and philosophising in the backroom of a liquor store, about the demise of the old neighborhood in which we live, and all the while the outside traffic heads north away from the city, the school kids in new uniforms marching by in scattered ranks, Mitsubishi Electric workers cycling home under greasy collars, ancients walking their dogs to nowhere in particular. The city winds down, the bathhouses fill up and dinners are served, beer bottle caps lopped off and TVs revved up. Another day gone. Kawabata-san burps. “Nothing lasts forever.”  What my paper doors used to look like. What my paper doors used to look like. For 15 years I’ve borne witness to the slow demise of a traditional neighborhood, the old houses being pulled down to make way for tax-effective car parks and smaller, more compact houses built of shiny, weather-resistant materials that make them look like cheap toys from Guangdong. “Many see old not as ‘classic’ but as unfashionable and inefficient,” Kawabata-san says, refilling our glasses. “The traditional Japanese townhouse is too hot in summer, too cold in winter, too dark, too airy, too noisy in typhoons, too quiet when it snows, too hard to maintain. Me, I love mine!” And me, mine. Yet, as new houses rise around us, I ponder the fate of my 100-year-old mudwall-and-tile abode, built in 1916 by the hands of master craftsmen. From the street it looks haunted. There’s a ‘pissing pole’ for local mutts outside, a crapping gallery for the crows in the power lines overhead, and twice a week, residents deposit their garbage bags (neatly) for collection along my south wall. I can replicate the roar-and-chomp of the midnight garbage truck perfectly. Ask me next time. I have come to favour its weather beaten facade, coarse tatami mats, creaking stairway and winter sunlight which streams through the holes in the paper doors. It's the tilt that worries me. A ping pong ball rolls across the floor from north to south at speeds which grow faster each year. Maybe it's time to join the slow bleed of the Good Hood and leave... I repapered the shoji sliding doors the other day, and the fusuma paper doors, and the amido fly screen netting that flapped against the window all winter. These are jobs designed to give you gorilla knuckles and a Quasimodo stance. I won’t miss them. One day this house will crumble and return to the earth, or to the Matsui Demolition Company which will bring in their ‘Komatsu Claw’ - a tracked house-munching machine that rips and shreds for a living. I will have to search the world wide web for a new dwelling, and a new ‘Good Hood.’ “Nothing lasts forever,” Kawabata-san says, looking at our empty beer bottle. The mountains behind Himeji look promising; cooler in summer with a view of the sweltering sprawl and glowing metallic centipede we call the shinkansen that passes through the city. Wherever I hang my hat in the those mountains, I will take pleasure in rolling the ping pong ball one last time. From the top of my street. Next week: The writer takes Himeji's Train to Nowhere.

1 Comment

Kevin

4/24/2014 12:10:50 pm

Ah, you captured the old mud pagoda brilliantly!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed