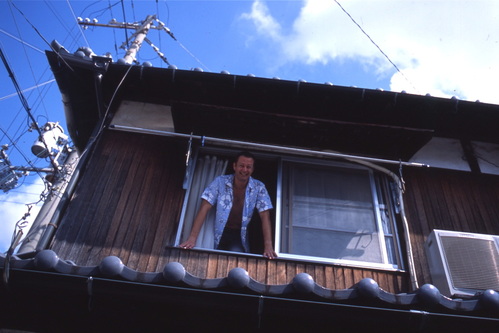

Last week I told YOU about the smells of the Good Hood, the crazy potpourri of soy sauce, Tahitian Lime hair tonic, rice paddy water, dog piss and yakitori smoke that defines the traditional neighborhood where I live. My house does not contribute to this because noise generation is our speciality: kids screaming, meal pots clanging, bath toys ricocheting, shouts, screams, whistles, mixed with the sounds of Marvin Gaye and my six-year-old singing Jingle Bells. Just what goes on inside The Foreigner’s house? My elderly neighbors can hardly imagine. But let me talk about the building itself which contains this madness. It’s a traditional Japanese town house made of wood, bamboo, mud and heavy kiln-fired roof tiles, built in the year of Meiji Emperor’s death, 101 years ago, and my home for the past 14 years. It rises two stories, with tatami rooms on each floor and paper doors dividing them. There are also tokonoma alcoves for hanging scrolls and psychedelic crayoned Father’s Day portraits. Few buildings of its likeness still stand in the Good Hood. Many have fallen to the wrecking ball, only to have risen again as high-tech ‘earthquake-proof’ homes with all-weather exteriors and fake wooden floors which hum with robot vacuum cleaners and plasma screen walls. Such homes you must grow into. Traditional Japanese houses, on the other hand, grow on you; and I’m not talking mold either. It’s not the creaking stairway or the earthen walls which shudder in typhoons, or the paper sliding doors which rattle like old bones in earthquakes, or the hidden gaps in the tatami mats which offer a revolving door service for insects great and small. No, it’s more simple than that; it’s the natural materials and the atmosphere they create. The smell of tatami, the smoothness of the tokonoma wood, the diffusion of light through paper doors and the shifting breeze about the engawa (veranda) that Japanese like my old friend Ono-san appreciate. She says traditional mud walls breathe better than plasterboard and to never underestimate the strength of natural wood beams in an earthquake. With each year passing year, however, each typhoon and long hot summer, a little more of this house returns to the earth and the air and a little more energy and ingenuity must be expended to keep it inhabitable; I corked the walls with my socks during the last typhoon and re-papered the sliding doors with ‘plastic paper’ to stop my son from punching them out. But there are some tides that can’t be turned, like the ping-pong ball which rolls smoothly from east to west without any coaxing, indicating the house has a serious lean. Unlike me, it’s on the move. A final word on the non-human inhabitants. A gecko stands guard over the front door at nights, goes by the handle, Ralphie. Mosquitoes that give him the slip are dealt a heavy hand by us humans. The white ants have been driven off, the slugs banished and the insect world now favours the arachnids--enormous yoru-gumo spiders which roam the tatami on hot summer nights. We call them the Roach Rangers. Before I forget, some years ago two English teachers who lived in this very house discovered a snake in their squat toilet. At first they were suspicious and looked at eachother accusingly, but realising it was alive, quickly photographed it for the record and dispatched it with jerk of a flush chain. Like many newcomers to the Good Hood, it’s easy to take a wrong turn and get yourself lost. Let’s keep with the animalia topic. Next week: The Good Hood Runs Wild.

1 Comment

|

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed