|

A long time ago (250 years thereabouts), a powerful dude named Sakakibara Masamune decreed that the people of his castle town slip into something more comfortable and shimmy downtown for a good time. “Do what?” his attendants asked. “Throw a party, you monkeys! I’m outta here!” Indeed he was, off to rule another fiefdom, but not before starting a tradition that would fill the fine streets of Himeji with colourful summer kimono (ゆかた, yukata), octopus dumplings and (a little later) skyrockets and riot police for three days a year, every year thereafter. More than just a celebration of the highly functional yukata, it’s a fashion show. Women’s yukata colours are brighter, patterns livelier, and shock! horror! hems are rising. The elderly women of the Good Hood shake their heads and click their tongues at these parading young things in mini yukata; the young fellas just nod their heads and knock themselves out with their tongues. The Yukata Festival, held June 22-24 every year, also celebrates the rainy season. That’s right, it is the WETTEST time of the year (news just in: no rain forecast for June 22-24th) which doesn’t stop several hundred thousand people from choking the streets and alleys south of Himeji castle with coin to spend on cold beer, toys and tasty treats. There were once more than 800 stalls, erected and manned by a small army of itinerant carnivaleers called tekiya. The big hand of City Hall has nearly halved this number in recent years, in order to manage the heavy crowds. The effect, as always, has been like squeezing a tube of toothpaste - same crowds, smaller space. Word on the street is that the tekiya are in cohorts with the local yakuza; others say that’s an unfair image and that the stall holders are just abiding by a ‘system’ which takes a nice slice of their earnings and hands it to the mob. Let’s call it a ‘licensing fee’. The City seems OK with this as it ‘stimulates’ the local economy and frees up their rubber stamps for more pressing matters. Times have changed since I tagged along with some English teachers to my first Yukata Festival 20 years ago. Then, youth gangs flocked from all over the province to wage theatrical (and sometimes violent) running pitched battles with their rivals on the city streets. Hard to believe in peace-loving Japan? Well listen to this: watching riot police get pelted with skyrockets, drag troublemakers off to paddy wagons by their orange hair, and see the odd motor scooter get barbecued, reminded me of the Costa Rican fruit vendor riots of ‘91 (Yes, I was in Costa Rica in 1991). Cheap entertainment for the masses, poor public relations for the police, not exactly a festive family affair. That’s all gone. The police have changed their tune. They now use subterfuge and infiltration tactics, clever stuff like putting dozens of plain clothes officers into the crowds to catch troublemakers on digital camera or video. Maybe this has worked, or maybe the young punks have just gotten older, gotten married and gotten a job, because the Yukata Matsuri IS now a family affair. ‘Smokin Joe’ Matsumoto, the old kitchen gardener who lives on my street in the Good Hood, will be taking his grandchildren again this year. Those long sleeves of his faded yukata will be sure to hold a pack of cigarettes, a lighter and some coins for cotton candy. My old friend Ono-san won’t be going; she thinks it’s too crowded, too noisy, the food tasteless and too expensive. “I’m saving my yukata for the fireworks festivals,” she says. If YOU go, be sure to drop by the Ghost House at the edge of Otemae park; it has been a going concern for years, adept at taking your money and scaring the beejeezuss out of you with the screams of other teenage patrons. They say a good ghosting chills you out during a long, hot Japanese summer. Personally I’d prefer a cold beer...

0 Comments

The legendary Toshiro Mifune grooming himself before stepping onto the set The legendary Toshiro Mifune grooming himself before stepping onto the set Sometimes good things can be found in the most unlikely places. For the best shave in my city, I go to the hospital. The Himeji Junkanki Centre Hospital, to be exact. This mysterious facility hides in the hills south of the train tracks and is only known to people with heart conditions, poor blood circulation or a poor sense of direction. Down a hallway, in a warren of hallways, past its blood drawing room, stomach camera room, X-Ray closet, a cafe of philosophical waitresses and a kiosk which sells everything for double-and-a-half, at the very end, stands a small barber shop. The sign over the door should say ‘Style with a smile’ or ‘Life is short, but our buzzcut is shorter’. Instead it just says “Barber”. On a busy day the wheelchairs are backed up around the corner. Waiting time is short, however, on account of the mostly elderly patrons who don’t have much hair to speak of. It's not the cut they come for anyway; it’s the ‘old school’ shave. I haven’t been around long enough to know what ‘old school’ means, but to recline in a classic Takara-Belmont barber chair with the tang of Tahitian Lime hair tonic in your nostrils and feel the liquid smoothness of an Iwasaki straight razor rolling across your chin and cheeks, is to savor one of the great intimate pleasures of Japan. A shave at the Junkanki Centre Hospital Barbershop is also my chance to step out of a lightspeed lifestyle for fifteen minutes, to drift off into a hot-lathered land where the hustle of a hospital sounds like a far-off cocktail party through which white-uniformed stewardesses push trolleys of clinking martinis and...be brought back to earth by the jolt and jerk of the chair, a brisk shampoo and a scalp rub which leaves me wondering where I am, what time it is and... There are two staff; an elderly man with a voice that sounds like a food processor full of thumb tacks and a middle-aged woman with a voice that doesn't. They share the glass shelves of scalp tonic, tubs of baby powder and hair wax, double-edged razors, clippers, a steam oven filled with hot towels, and a transistor which radio plays Okinawan ballads in the morning and baseball in the afternoon. For some reason it’s the woman who always cuts my hair and shaves me. She tells me she has two young sons and two jobs. I know she works hard and her shoulder massages make me remember it. I’ve often wondered if her second job is dough rolling in a noodle joint, or maybe she has a black belt in shiatsu? I will ask her next time. We talk about our kids mostly, our neighborhoods, the seasonal festivals and the different viruses currently circulating at the kids’ schools. She knows my local liquor store owner (he’s also her customer) which means our seiken (world) really is semai (small), which is really the essence of Japanese community spirit. It’s this reassurance and safety 'by association' that gets you through doors and gets you good service, which of course is a two-way street. I always tip ten percent. Almost all the old neighborhoods in Himeji have a barbershop. They are considered an ‘essential local service’, and seemed to have outlasted the rice millers, tatami mat weavers, coffee shop owners, butchers and fishmongers. The barber shop also remains a kind of ‘bush telegraph’ where (mostly) men go to chew the fat and shoot the breeze, and some not to get a haircut at all. On my street in the Good Hood stands the Funabiki Barber Shop with its red and blue spiralling pole and cheerful snip-snipping sounds emanating from the tiled floor inside. It’s run by a family of barbers who rise with the sun and are still hard at it after dark. In Autumn, their kids practice taiko drumming with mine, and send them to me with bag fulls of fresh wakame seaweed and strings of onions. Once, I went for a haircut with a hangover. I fell asleep in the chair and awoke with a shaven forehead, ears and nostrils smooth, and a coiffure like a professional Japanese baseball player. There is only one other place I have ventured into in Himeji. It’s called Royal, and I won’t be going back. Royal is what’s known as the ‘shearing sheds’ in the Australian vernacular. It’s Sweeney Todd without the head-rolling and meat pies. A long line of chairs face a continuous mirror and manning these are men who might have once been pet groomers, tree doctors or failed ramen chefs. Golf is a popular sport in Japan, although to play eighteen holes can be cost prohibitive. But if you really want eighteen holes, it will only cost ten bucks at Royal. The Haru-Ichiban (春一番, First Wind of Spring) is afoot. It’s at this time of year, when my nose runs like snowmelt and my eyes itch with hay fever, that my finger hovers over the 'book now' button for a low-cost carrier going anywhere between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, any place where cedar pollen and Gobi sand, which the last of the Siberian northerlies bring to western Honshu, have no local translation. Problem, as always, is funds. You can’t get on the big silver bird without a big silver coin. So, there will be no Bintang in Bali, Sling in Singapore or Singha in Siam, to celebrate winter’s end this year, boo-hoo. About a month ago, however, something fortuitous happened. I discovered a large greenhouse beside the mountain where I work. It is used by the Faculty of Pharmacological Science to grow medicinal plants for research and is tended by a retinue of elderly men in powder blue overalls who water and weed and keep the insects in check. The good thing about March is that there are no university classes; the researchers are all off in Borneo or Guatemala, or wherever it is that they go to study medicinal plants, give medicinal presentations and try local 'medicine' (for medicinal purposes only), which leaves myself and the powder-blue people to enjoy this pollen-free paradise in peace. When I first stepped inside the greenhouse, it was mid January. Outside was a big fat zero; inside, the lush 25 degrees had me loosening my collar and humming “April Sun in Cuba” while I settled down to read my lunchtime paperback. It was Charles Bukowski’s Post Office, a winding yarn about a guy (himself) who skives off during working hours to go gamble on horses, drink, chase women and write bestsellers. Now, the powder blue people disappear around lunchtime, so after a few weeks I started to feel a little lonely sitting in this jungle all by myself. To remedy the problem I sent out an invitation to my long-time friend, the old kitchen gardener who lives up my street, Smokin Joe Matsumoto, asking him to join me. I thought he might enjoy sitting around and telling yarns about ‘old Japan’ beneath the Piper longum (peppercorn) bush, Tamarindus indica (tamarind) tree, Cymbopogon (lemongrass), Zingiber officinale (ginger), jasmine and orchids, but I’m yet to hear back from him. I’d like to show him the Rauvolfia serpentina (Indian snakeroot) which, I've since found out, contains 200 known alkaloids and is used as a traditional antivenin to treat snake bites in India. A little more reading and I discovered that Alexander the Great used it to cure Ptolemy of a poisoned arrow injury; Mahatma Gandhi also took it as a sedative (for stress? yeah, right). Snakeroot contains reserpine, an antipsychotic, antihypertensive alkaloid, which was once used by Western medicine to treat high blood pressure and schizophrenia. It is still one of the 50 most used plants in Chinese medicine. I will knock on Smokin Joe’s door again. He has a bear-like tendency to venture out in late March when the fragrance of the plum and cherry blossoms carries on the Haru-Ichiban. On second thoughts, I fear our little ‘green-ins’ will attract attention. If other administration staff find out they can take their coffee breaks in the tropics, it might get a little too hot in there. I must be careful. The other day I finished the Charles Bukowski book and searched my shelves for the next thing to take to the greenhouse; I passed over Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (too dark), Spencer Chapman’s WWII soldiering-in-Malaya memoir The Jungle Is Neutral (too long), and Peter Matthiessen’s missionaries-in-the-Amazon adventure At Play in the Fields of the Lord (too much drama). In the end, I picked out an old favourite, Eric Hansen’s Stranger in the Forest, about his journey on foot from one side of Borneo to the other. So with coffee and book in hand, and whistling Guns ‘n Roses’ “Welcome to the Jungle”, I returned to the greenhouse yesterday. Only to find it locked. The paradox of living in a traditional high-density Japanese neighborhood is that on some days it feels like there is no-one living here at all. Granted, summer has begun and the heat and humidity are oppressive, which means the narrow crooked streets of the Good Hood are quiet, save for the happy hum of Toshiba air-conditioners and the sound of a far-off water gun battle. But when the sun sets, the neighborhood broadcasts a new symphony. I can’t say if this is the true nocturne of night-time across Japan because I’ve lived on the same street for 18 years but I suspect so, only probably louder in Osaka. Let me describe the aural clock I live by: sunset brings the sound of bicycle bells and screaming brakes as workers pass through my neighborhood on their way home to the burbs; then comes the soft-shoe shuffle of my elderly neighbors carrying their garbage bags to the collection point outside my house. Later, the tom cats will tear these open and fight each other for the fish bones, hissing and screaming, and maybe leave a little surprise on my doorstep. Thankfully the singing drunks who come after will scare them away before those surprises pile up. These singing drunks are mostly businessmen, sometimes on ‘requisitioned’ bicycles, whose hard-earned cash is sometimes also ‘requisitioned’ by the ladies on Salt Town Street. But that’s another story. Around midnight the security guard who lives to the north of me arrives home. I know exactly when he arrives because his dog, “Pudding”, announces it. On summer nights when the air is still and hot, I lie awake on my futon and listen to the off-duty security guard climb the wooden staircase to his balcony where he proceeds to tear the tabs of a half-dozen cans of beer. I also hear the clickety-clicking of his empty cigarette lighter and the crackle of saltpeter as 4,000 chemicals burn between his fingers. On Sunday mornings he plays Harry Belafonte up loud, and now I ask you, how would you like to awaken to “The Banana Boat Song" ("Day-O”) or some other Caribbean drinking ditty at seven in the morning of your only day off? But back to the clock. We are at midnight. This is when the junk mailman’s farting Suzuki rolls into town and the sound of him jockeying this pile of nuts and bolts through the alleyways, stuffing letter boxes full of ads for private detectives (the wives have heard of Salt Town Street), summer futons and cheap haircuts, deprives me of another ten minutes sleep. Yes, there are nights when I envy the hard-of-hearing, these old-timers who can drop their blinds at eight-thirty and rise with the sun to water their morning glories with eight hours of uninterrupted sleep in between. Three months ago, new neighbors moved in. Like rust, they don’t sleep either. Rust doesn’t sleep because science says so. These people are very unscientific. They might even be from Tokyo - the city of a million and one insomniacs - but I give them the benefit of the doubt and say that it takes time to acclimatise to new surroundings. So I will endure the teenage daughter who sings Japanese anime songs at one in the morning from her upstairs window, and the father who stays out late and returns to a berating from his wife whose late-night TV drama he’s interrupting, and finally the hot water shower system which sounds like a high-octane dragster splitting the dead of night wide open. Thankfully my new neighbours don’t have a dog named Pudding. They have turtles, and like all turtles they started out small (at a ‘catch-em-yourself’ festival street stall). Now they have grown so big that the family last week told me they are going to build a concrete enclosure and sink a well in the backyard to give their pets fresh water for life. It costs ¥500 ($4.80) to play the festival turtles. It will cost my neighbors another ¥500,000 ($4,800) to house them. I like turtles. Turtles don’t complain about the heat, they keep regular hours, and they don’t sing or smoke. They just live long SILENT lives. Saw my old friend Smokin Joe Matsumoto the other day after a winter’s hiatus. Like the old bear he is, the scent of a Japanese spring had teased him from his lair and back to his plot of earth beside our waterway, the Semba River. I’m guessing those endless tempura lunches and hot pot dinners all through the long cold months had expended his supply of homegrown vegetables and there was nothing for it but to go break the soil for a new planting.

For the record, Smokin Joe is not only a damn good cook, he is a man of indeterminable age and boundless wisdom, AND he has a right arm that could kill a watermelon thief with an eggplant at 50 paces. Like the grasshopper in the Aesop’s fable, he is also a prodigious and pragmatic food producer—a ‘celery man’ in a nation of ‘salarymen’—working for his garden, not a company, reaping the bounty for himself, not his boss. Now spring has passed and the warmer temperatures mix with rain to unleash green fury on our neighborhood. Not so long ago I awoke to cherry blossoms outside my window; now it’s Day of the Triffids; creeper, weeds and bamboo swallow the old and derelict houses and will do so until distant relatives of their deceased (or institutionalised) owners can fight back with hand saws and weed cutters. This does not bother the tadpoles—there will always be broken flower pots and abandoned bathtubs filled with rainwater for swimming lessons. After, the paddy snakes will decide the quick and dead. Early evening when the western sky is still bright enough to see by and the bats are skirting and diving over the Semba River is when the kitchen gardeners are most active. Up and down the river they muddle about in their small plots of land, tossing buckets attached to ropes into the current to top up their bathtub water tanks for the long, hot days ahead, then maybe puff thoughtfully on a cigarette, like my mate Smokin Joe, or put a sly beer down the hatch before bundling their bounty onto a bicycle and peddling home to more beer and baseball on TV. These constant gardeners are the last hold-outs in the war against the Machines, the construction companies and their excavators, and the real estate agents so keen to turn productive earth into pavement-for-profit—parking lots, that is. Last year Smokin Joe was robbed by watermelon thieves. They came in the night and rolled off his best. Another day he noticed soil missing and filed a report with police. The cops call in occasionally to say they’re “still working on it” and together Smokin and I try to imagine the headlines when they solve this big one: “Soil Gang Foiled” or “Cops Hit Pay Dirt” or “Quiet Earth Found.” When the harvesting begins, the bounty reaches everyone. My neighbours, the affable Funabiki barbers, brought me a string of giant onions yesterday and last week a bag of eggplant and capsicums was left swinging from my door by an anonymous friend. Sometimes the old woman who feeds the grey heron on the Semba also feeds me—with a great dirty daikon from her veggie patch. Smokin Joe, by his very nature, is a generous man, proffering bags and baskets of vegetables as the seasons progress: strawberries in May, capsicum and broad beans in June, sweet peas and cherry tomatoes in July, corn in August and the culinary calendar rolls on until December arrives and Smokin goes into hibernation with a crate of sake and enough cooking oil to see him through the winter. In the meantime I look forward to June. June means cucumber: cucumber for breakfast, cucumber for lunch, cucumber for dinner. There’s nothing like a chilled cucumber with salted kelp served with a bottle of Kirin lager at the end of a hot June day. Smokin Joe would agree. Rain shrouded the city yesterday. You could almost hear the creaking sounds overhead as the cool Siberian air flow played tug-o-war with the warm southerlies rising from the Philippines. Today the Good Hood is warm and heavy with the smell of spring: the fragrance of sakura and daphne, the odors of a fast moving river, wet bamboo and grilling sawara (鰆), a kind of mackerel which spawns in the nearby Seto Inland Sea during spring.

But last weekend a more ominous smell muscled in on my neighborhood; the kind that strikes fear into the hearts of residents of all traditional wood homes across Japan, the bitter tang of charred wood and scorched earth. It happened on a sunny Saturday afternoon as I was driving home, ironically, from the DIY centre after buying three new smoke detectors for my house. Flashing lights of eight fire trucks, a swag of police cars and cops on every corner met me at the entrance to my street. Access was blocked by fire hoses and Himeji’s finest waved me on with a ‘nothing to see here folks’ gesture. But there was something to see--my bleedin house! Over the rooftops, in the approximate location of where I drink beer and watch TV every night, dark plumes of smoke were rising. I checked my phone: my landlady had called three times. My pulse leapt from the starting blocks. Crowds of gawkers stood on the street corners, most of them familiar, so when I lowered my window to ask, “Whose? Whose? Whose izzit for Chrisssake!” I got an answer which released a sigh of relief you could have heard all the way to the Okinawan islands. I have yet to find out what caused old Mrs Nakao’s house to burn down. I talked to the neighborhood boss, whose own wood-and-tile house stands next door, but he didn’t know. Maybe she dropped a hot iron to catch a phone call, maybe she fell asleep to an afternoon Korean drama with a ciggie in her hand, maybe she was drinking Pimms and soda with The Doors turned up and Jim Morrison really got to her. Like the boss, I don’t know. But I did hear that the fire started in her annex and swept down the hallway so fast that she only had time to grab her cell phone. The fire officers wouldn’t let her return to snatch any mementos and the cops stationed a patrol car outside overnight to deter looters from doing the same. In olden days Japan when a house burned down, neighbors would visit to pay money and condolences called kaji-mimai (火事見舞), a tradition which continues in older neighborhoods including ours, where ¥10,000 is the going rate and no return ‘gift’ is required. So thank Buddha for this April rain which hangs in grey veils over my city, gushes and gurgles through the cracked spouting of my 100 year-old house. The cold and waterless winter has passed, meaning there will be no more kerosene tankers working the morning streets with their ice-cream-van jingles, no more village fire trucks making the Sunday night rounds warning denizens to turn off their kerosene heaters and appliances before bedtime--and hopefully no more fires. My old friend, Ono-san, told me her story over barely tea the other day. About a year ago she and her son dozed off beneath the kotatsu one evening while watching TV. Some time later she was woken by the ringing of a Buddhist gong in the next room. Ono-san went to investigate. When she entered the family altar room she was met with the smell of smoldering tatami. In front of the family’s Buddhist shrine the incense urn had tipped over and the incense had begun to burn the reed mats. She quickly snuffed it out and woke her son who promptly asked the million-dollar question--who rang the gong? Like I said, thank Buddha. Himeji was firebombed during World War II. Some say Himeji Castle was spared because it served as a navigation point for the American B29s heading east to hit the aircraft factories in Kobe, but they razed the south side of Himeji for good measure anyhow. Abe-san, an elderly student of mine, witnessed this ‘scorched earth’ policy first hand. As a seven year-old she fled to the mountains on the night her neighborhood was bombed and she recalls looking over her shoulder at the “beautiful fire sticks” cascading from the low flying planes before someone grabbed her arm and dragged her onwards to safety. Thankfully the Good Hood--my home-away-from-Australia for 18 years now--was largely spared the wrath of the B29s. Older houses still bear the traditional talisman meant to ‘repel’ fire, like the kanji character for water (水) which is embossed on the clay tiles at either end of a roof’s apex, or the half-carp half-tiger figurine, called shachihoko (鯱鉾), which sits atop it. Upcountry, in the paddy lands where some old farmsteads still use indoor fireplaces, a wood carving of a fish might hang above the ash bed to ward off ‘evil’ sparks. It is difficult not to think about old Mrs Nakao’s house lying there, a village block away, reduced to a pile of wet ash and soggy cinders. It is difficult not to think about it lying in my futon at night or getting dressed for work each morning or towelling off after a bath in the evenings. Because the one thing I forgot to do before leaving my house that fateful Saturday afternoon was to bring in the laundry and shut the windows. Now, when my students’ nostrils twitch and they glance at me strangely, I tell them I’m wearing the latest cologne for adventurers and outdoor enthusiasts--Eau de campfire by the House of Nakao. A lot can change in the space of a few weeks. One day you live in a house on the sunny side of the street, the next, the Tower of Babel is rising over you.

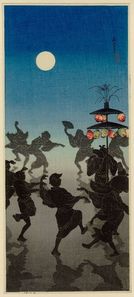

Once again ‘nothing lasts forever’ explains it all. From dawn till dusk my 100-year-old townhouse is now masked in shadows. I want to tell my new neighbors that laundry doesn’t dry as well under moonlight. Or that my Vitamin D deficiency is giving me soft bones and muscle weakness. My new neighbors? The daylight robbers, I have yet to meet them. They are a mystery; soft-shoed ghosts who deposit ‘sorry gifts’ in my entrance way - boxes of neatly wrapped rice crackers - perhaps because they are afraid, or ashamed to have stolen my sunshine, or just unsure of how to approach a ‘foreigner’ nextdoor. Enough rice crackers, already! The Shinto gods are not on my side. When the newly cleared plot was sold, the owners held a ‘ground breaking’ ceremony, or jichinsai (地鎮祭). They wheeled in the spiritual artillery - a Shinto priest in full garb - to conduct the blessing. This I watched from behind my curtains, cracking my knuckles and grinding my teeth, as small piles of salt were placed at the four corners of the plot to ward off evil spirits. Could the big white man from D’under be an evil spirit? I surely drink spirits and my socks smell evil from time to time...I’ll ask next time we meet. When construction began the stone masons were first to arrive. Up went the boundary wall in somewhat of a medieval gesture. Then came the foundation laying team, a two-man outfit in camo-print monpei (Japanese knickerbockers) who said nothing, just went about their concrete pouring and cigarette smoking until the builders took over. The builders are still here, arriving each morning at 7:30am to sit in their mini trucks and drink hot canned coffee and read comics until a few minutes before 8am when they assemble to get the day’s orders from the boss. Lip-reading, I imagine the conversation goes something like this: MINIONS: “What’s the plan, boss?” BOSS: “Build it to the sky.” And so, as the winter days wear on and snow sometimes falls and the Siberian wind blows, the Tower of Babel rises. Rises to a symphony of staple guns, power grinders, band saws, hawking and harking and FM radio. A three-storied house beside a neighbor with just one sad story to tell. At night I lie in my futon and listen to the silence and wonder if the gods will punish the arrogance of the humans who think they can build a tower to the sky, steal the sun and rob a man of his view of a 500-year-old samurai castle. I am trying to understand a paradox here: Japan’s population is falling but why are the number of new houses rising? Do all young home buyers want new Western-style houses with composite kitchen flooring, porthole windows and a shiny name plaque? What about maintaining traditional houses made of natural materials which ‘breathe’ in summer, diffuse sunlight in winter and smell of tatami reed and cypress wood? I think the answer is elementary, Watson: modernity equals ‘progress’ and old Japanese homes are just too dark, cold and old world. I saw an interesting sight once, a building team huddled around a plan model of the house no bigger than a doll’s house, which they were about to build. And so it followed that these burly men who eat wood chips for breakfast and shave themselves with power grinders did just that: they built a doll’s house. INTERLUDE: More ‘sorry’ gifts arrived yesterday. So, relative to the height of the Tower, the pile of rice crackers in the corner of my room grows. Well, I could say life sucks. I could start drawing up a small business plan for a mushroom farm - I hear shiitake love dark, damp conditions - and I could get business cards with “artisanal shroom farmer” printed in both Japanese and English. Or, I could just saddle up Old Moe and join the tumbleweeds blowing south, hit the highway with a fistful of yen and a box of rice crackers. If you meet a tall stranger on his nag, unshaven, in a poncho and chewing an old rice cracker, it won’t be Clint Eastwood. It has been a good 18-year partnership, this house and I. We’ve survived the parties, earthquakes and typhoons, the paddy snakes in the toilet and the swallows which carry off the earthen walls each spring, and though a little worse-for-wear, I’ve always believed we’d be a team for as long as the sun kept rising. But now, as I tap out these words, I feel like a war reporter filing his last dispatch before the fall of Saigon; my room is shaking, the window panes are chattering, the paper sliding doors dance in their grooves. Less than ten metres from where I sit, a CAT hydraulic excavator is crunching my neighbor’s house like breakfast cereal. “Nothing lasts forever” has been the ongoing premise/prophecy of these blog posts and today it is again being fulfilled. The enemy is at the gates. It’s a “no-hard-feelings” enemy, unshaven and Camel-smoking, but otherwise professional. I chatted with the CAT driver, a short, squat man with a gold tooth which glimmers whenever he says “Good morning.” When I asked him if I could keep the hydrangeas on the other side of my boundary line, he lit up a Camel, flashed some gold and said, “Lemme talk to the boss.” The big boss came around last night. He came bearing gifts: a box of cakes and custard puddings and an apology for the noise and earth shaking, and said, “Yes, we will save the hydrangeas. We’ll transplant them for you a few metres to the north.” I took the cakes and said, “OK, thanks.” As my aged neighbors have passed on and left their traditional mud and tile homes to the whims of distant relatives, “nothing lasts forever” is still the easiest way to explain the slow but sure demise of this neighborhood. The Electric Company’s dormitory building down the street was felled five years ago, Fukumizu-san’s house razed soon after. In a few days, where the CAT chews into my neighbour Toyoda-san’s house, a vast expanse of freshly pressed earth will extend all the way to the Funabiki Barber shop. The breeze will flow easily, the smell of Tahitian Lime hair tonic stronger, and the first rays of sunlight will prise open my eyes where once they couldn’t. I watched the demo team tossing Toyoda-san’s roof tiles into the dump trucks the other day and wondered about the fate of the rat snake that lived beneath them in the roof cavity. Had he skipped town? Had he joined the growing number of pets-on-the-run? Had he eaten any of them? My Canadian neighbor has moved to the bright lights and big city in the East; his house stands empty awaiting a new tenant. Across the street, Nakanishi-san’s house is slated for demolition in the New Year. I got a gift in advance for that earth-shaking. This neighborhood has become a mouth full of old teeth waiting to be knocked out, then implanted with shiny, new things. Meanwhile, the local real estate agent walks with spring in his step. His collar is crisp, his hair gleams obsidian like his town car; he is cleaning up. He knows that when his house-selling clients fail to close a deal after a year, he will make them an offer they can’t refuse. He will re-package their property, crank up his marketing machine and turn a tidy sum when a fish is hooked. And the fish are biting; young couples cruise our narrow, stop to take photos, prod the earth with their toes and sniff the air. In my own uncertainty about the future, I have joined them. I inspected a house upcountry the other day; not a house, more like a whole village - a sprawling farmstead with so many interconnecting rooms, storehouses and lofts which opened onto each other, it was like stepping inside a Chinese puzzle. In the end, it was just too big, too full of ghosts and stories I didn’t know the end to. It was an enterprise, not a home. So, is this the last Hoorah? Probably not. This house will probably stand for a few years longer. Matter of fact, the landlady has offered to sell it to me. To be honest though, the time has come to start anew. Time to let old carbon return to the earth and let it rise anew. My resolution for 2016 will be to make a decision. Then again, nothing lasts forever, not even a resolution.  Bon-odori woodblock print byTakahashi Shotei Bon-odori woodblock print byTakahashi Shotei Beebedy-beep-beep~ Air traffic over Japan will be heavier than usual this Saturday night. Across the archipelago, over city, town, village and paddy, spirits of all ancestors will return en masse to the Earthly world. Obon will be a blast (for them): three days of lurking and lingering in incense-filled rooms, with the pinging and bonging of altar chimes and the hum and drone of the visiting Buddhist priest’s sutras to venerate and refresh their retired (and tired) souls. In addition, the living must leave their cool, dark homes and venture out under a blistering August sun to pay further homage. This means, for my old friend Ono-san and my old kitchen gardener mate Smokin’ Joe Matsumoto, a trip to the cemetery. City of the Dead, Spirit Suburbia, Hallowed Heights - call it what you will, but here in Himeji city, Ono-san, Matsumoto-san and half a million more know it as Nagoyama: an entire hillside combed in long, neat rows of gravestones which rise to a Buddhist stupa at the summit. From here I would like to say that ‘on a clear day you can see forever’ but the mills of Nippon Steel on coast cause me to swallow my words. Small paper lanterns are lit and placed at the graves on the first day of Obon to ‘guide’ the spirits in - much like the runway lights of Kansai International Airport. Gravestones are then wetted and cooled with ladles of water and rubbed off, their are chrysanthemums changed, offerings made, incense burned and prayers murmured.  Party in Good Hood. Onatsu-Seijiro Festival, Himeji. Party in Good Hood. Onatsu-Seijiro Festival, Himeji. Occasionally a hard-up drifter might take liberties with the offerings of fruit, snacks and cans of beer and sake, there’s no law against it, but you won’t catch me peeling hot oranges and drinking boiling beer reserved for the spirits. Obon is a strangely eerie time. Cicadas fall out of the sky dead, crisp as beer snacks, the streets and alleys of the Good Hood, my home for 18 years, are suddenly lifeless, dreary even. Thankfully, Obon is sandwiched by vibrant summer festivals - in the weeks before and after, fireworks turn the nights into day and Himeji’s neighborhood streets fill with stalls and parades of dancing women in yukatas. And the Good Hood, despite its slow decline, partakes. Lanterns are hoisted high on the shopping street, yakitori and cotton candy stalls materialise and the courtyard of Keiun-ji Buddhist temple glows with candles and the cheeks of old shakuhachi flute players who have over-imbibed on beer. Children appear in yukata, followed by parents and hobbling parents’ parents, all eager to sample the night’s delights; for the kids, that’s mountains of coloured ice and for parents, an icy Kirin lager will do nicely thankyou. Obon also means the return to hometowns of old school friends, which in turn means you will be hard-pressed to get a table at any of the city’s burgeoning rooftop beer gardens around this time because of all the sodden reunioning. Seaside Japan empties too after Obon; kids suddenly remember the mountains of summer holiday homework they haven’t touched, while company workers trudge drearily off to catch a bus to somewhere they’d rather forget, dreaming instead of the past week’s seafood feasts, bikini girls and white caps of the Japan Sea or Pacific Ocean. And just like that, summer will have gone, slipped through our fingers. Melted away like a wily ancestral spirit. Flat as a teppanyaki grill this city of half a million might be, but in August it’s nigh as hot as one too. You know it’s hot when Fujimoto-san, the coolest cucumber AND the hardest working noodle chef on Otemae Street starts sweating into his dough. A little salt to taste? All good in this summer swelter, I say.

Horsepower beats pedal power in August. So, in a country where small is king, I will join the perambulating proletariat in compact, air-conned comfort. I call mine the “Little Red Rocket” (a Polo Volkswagen) on account of its candy apple red paint job, and “Little Red Heartbreak" on account of the money I have since paid for it in repairs. Still, it's the bee's knees for negotiating the labyrinthine network of streets over which Himeji sprawls and if this city were indeed a human body, with Himeji Castle the beating heart, I would live at the end of one crooked capillary, a street not widened since the last rickshaw drag race in 1901. There is no need for traffic lights here in the Good Hood - you simply cannot drive faster than a centegenarian doing a soft-shoe shuffle to the convenience store. And this is no place for goading six cylinders either - a Zen state of mind prevails, people motor about like they’re listening to the “Sounds of One Hand Clapping” or “Haiku Hits and Memories.” Even in August when you’d expect tempers to rise with the mercury, they don’t. Drivers nod and bow to each other, slowing to allow pedestrians to cross where there are no crossings, giving way when there is no legal (or rational) need, and allowing fellow motorists to edge into long traffic streams ahead of them for no good reason other than goodwill. Which is not to say that Himeji is driving Heaven. Hell, no! My facial muscles grip my skull each time I venture beyond the comfort zone of the Good Hood where I’ve lived for the past 18 years. An instructor at the Sanyo driving school where I took a refresher course years ago warned me. He said, “Himeji drivers are the second-worst in Japan.” “And the worst?" I squeaked. “Osaka,” he said, clicking his tongue and looking towards the east. “Fuhgeddaboudit.” I concede, some drivers a little too Zen in the head here. Zen-drunk even, when empty mind is overtaken by absent mind. There are drivers who park on sidewalks, leave engines running outside 7-Eleven while they do their shopping, run red lights, juggle dogs and babies and cell phones, and on the sight of any orange traffic light, they put the pedal to the metal. In Himeji, 10km/ph over the speed limit is deemed acceptable. You could go drive slower of course, but only the cops do that, which lends them an air of ominousness which I suspect they like. Civil servants with power exert it - even if driving a desk. I sat through a mandatory lecture at the Himeji Police Station, filled with the yawning and the young, grinding my teeth as the traffic wardens ran through the car accident statistics for the previous year. The atmosphere would have made an actuaries’ conference look like the last party on Earth. And the people who really should be there? The yakuza? No. The bōsōzoku (暴走族, literally “running-out-of-control tribe") motorbike gangs? No. The geriatric red-light-runners? No. In my mind, the greatest threat to humanity on the streets of Himeji is the 'young momma', the woman who is five minutes late for her son’s piano lesson. At her disposal is 2,500 ccs of hot-greased Japanese technical know-how, satellite-connected, TV-equipped, iced latte-filled and antsy-fumed. As a cyclist, I have been cut off at corners, edged into azaleas, brushed at signals and generally looked down upon from the captain’s chairs of these hot-greased family wagons all my life by these women. But not today, no sir. I’m looking up. Looking up from the air-conditioned comfort of my Little Red Heartbreak with The Police on full volume, singing “De Do Do Do, De Dah Dah Dah is all I want to say to you!" |

This Blog:What is the essence of a traditional Japanese neighbourhood? Writing from my home in Himeji, a castle town in western Honshu, Seaweed Salad Days distills, ferments, presents! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed